"Sirens" Songs: M'Appari

This is part one of a two part series about select songs from the “Sirens” episode. You can read part two here. (Part two coming soon!)

Stuart Gilbert, in his book, Ulysses: A Study, explained that in the view of the average Dubliner, music was an “essentially Italian art” and therefore it was common to refer to songs by their Italian names, even if they weren’t originally written in Italian and were typically sung in English. A prime example in “Sirens,” Ulysses’ eleventh episode, is the first musical set piece, featuring Simon Dedalus’ rendition of an aria from Friedrich von Flotow’s 1847 opera Martha. Originally performed in German, Martha was translated to English and Italian later in the century. We shouldn’t be surprised as readers, then, that while cajoling Simon, Fr. Bob Cowley reaches for the Italian first:

“Cowley sang:

—M’appari tutt’amor:

Il mio sguardo l’incontr…”

The aria’s Italian title is the first line that Cowley sings here: “M’Appari Tutt’amor.” The original German was “Ach! So Fromm, Ach! So Traut!”, while the English version is titled “Martha, Martha, O Return Love!” True to the conventions described by Gilbert, the “Sirens” aria is typically referred to by its Italian title, “M’Appari”, even though Simon sings the English translation by Charles Jeffreys from 1849. “M’Appari” features prominently in “Sirens,” but it has also popped up here and there in such disparate places as Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window, the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (sung by Gene Wilder), and the American adaptation of The Office.

Before we find ourselves drifting away on Simon Dedalus’ siren song, we should take a look at a few other musical allusions found in “Sirens” that add depth to our understanding of his musical selection. Earlier in “Sirens”, bronzehaired barmaid Lydia Douce briefly sings a line from a song of her own:

“—O, Idolores, queen of the eastern seas!”

This lyric comes from the song “In the Shade of the Palm,” from the musical comedy Florodora, a big hit in the early 20th century. Miss Douce makes an error in this lyric, however. It should go, “O, my Dolores” rather than “Idolores,” Dolores being the female lead of Florodora. You can hear the correct lyrics in this YouTube rendition of “In the Shade of the Palm.” The lyric she sings also references the “queen of the eastern seas.” Gilbert views the “queen of the eastern seas” as simply a Siren figure and assures us that “Miss Douce… like the Sirens, sings by ear, not by score….” Much like with Shakespeare’s family history in “Scylla and Charybdis,” this lyric and Miss Douce’s flub reveal the intricacies of Ulysses rather than anything about the source material. Scholar Zack Bowen identifies our Joycean “queen of the eastern seas” as Molly Bloom, queen siren of “Sirens,” and declares this song the first and most important siren song of the episode.

There’s a bit of preamble before Simon begins his performance for the ragtag assembly in the Ormond Hotel, making it all the more potent when Simon finally sings. Simon enters the bar with his companions Ben Dollard and Father Ben Cowley. Last we saw this trio, they were commiserating with Cowley about his landlord woes with the Rev. Hugh C. Love. It seems like a solution may be in the works:

“—Eh? How do? How do? Ben Dollard’s vague bass answered, turning an instant from Father Cowley’s woe. He won’t give you any trouble, Bob. Alf Bergan will speak to the long fellow. We’ll put a barleystraw in that Judas Iscariot’s ear this time.”

It’s time for the boys to let loose a bit. Ben begs a ditty from Simon, but Simon requires a little more gassing up. He deflects and requests a song instead from his friend Ben Dollard, the “base barreltone”:

“—Love and War, Ben, Mr Dedalus said. God be with old times.”

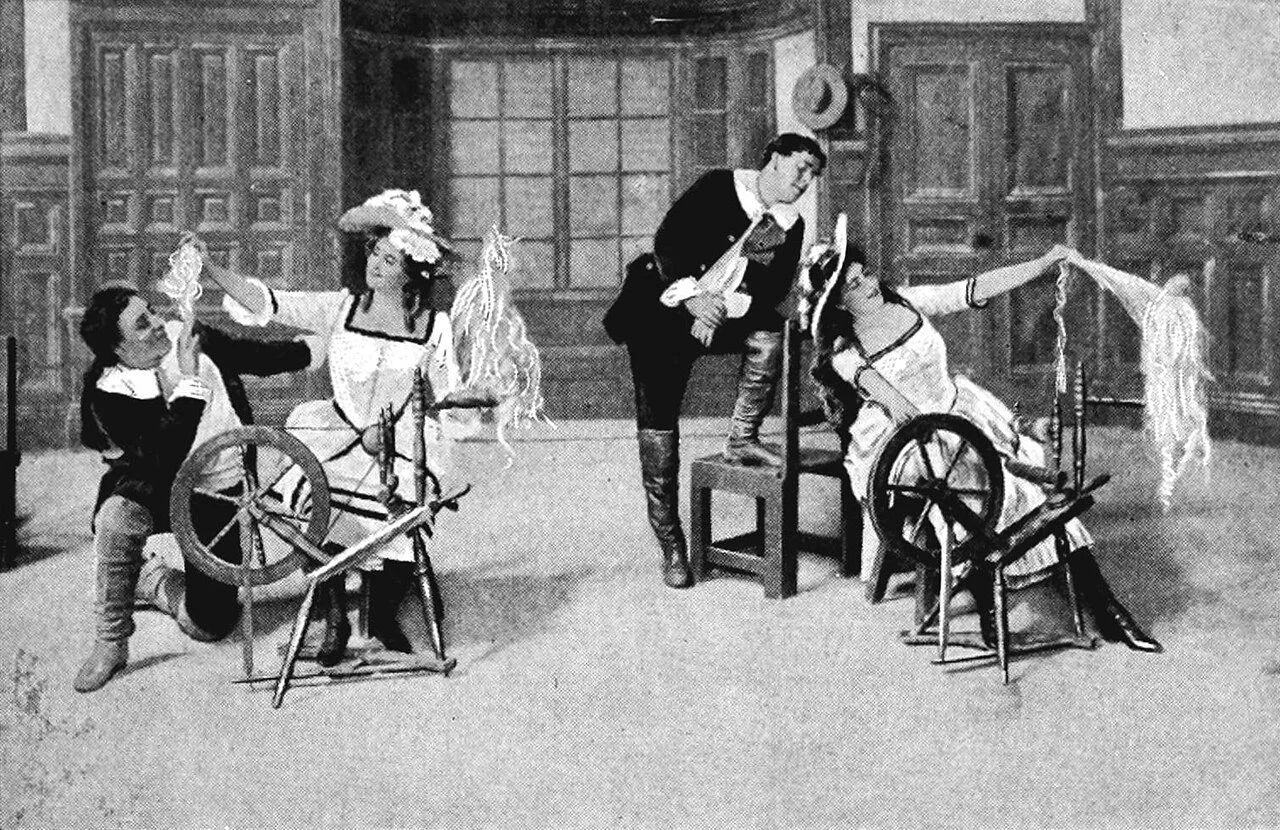

“Martha” in 1917

“Love and War” was a popular song, a duet for a tenor like Simon and a bass like Ben. The tenor part sings of love, while the bass sings of war, which is why Cowley later refers to Ben as the warrior. Scholar Richard Ellmann, in his book Ulysses on the Liffey, describes how Ben’s performance of this particular song sets up the twin themes he and Simon represent in “Sirens.” Simon will go on to sing “M’Appari” about lost love and Ben will sing “The Croppy Boy,” depicting an imagined scene from a lost war. Scholar Mark Osteen takes this interpretation one step further, expanding the theme to fully encompass both “Sirens”, an episode with love at its core, and “Cyclops”, a particularly warlike episode. Simon, Osteen argues, sings about the word known to all men, Love, and in the process inspires Bloom to take a stand for love in the next episode, “Cyclops”, even as he is threatened with violence at the hands of the Citizen. While the source (Simon) is anything but perfect, the message (Love) nonetheless strikes the right chord.

Next on the program in the Ormond is an aria from the opera Sonnambula called “Tutto é Sciolo”: “All is Lost”. Bowen notes that Joyce was fond of this phrase and thus worked it into this scene in Ulysses. It will recur here and then twice more in “Circe.” Bloom’s dinner companion, the drunken little costdrawer himself Richie Goulding, waxes rhapsodic about how much he loves this song and his memories of its greatest renditions. Bloom is also moved by Simon’s tenor, sweet as a thrush or a throstle (which also means thrush). “All is lost now” aptly describes several characters in this scene. “Bloom lost Leopold” looks across the table and sees this sense of hopeless embodied in his dining companion:

“Face of the all is lost. Rollicking Richie once. Jokes old stale now. Wagging his ear. Napkinring in his eye. Now begging letters he sends his son with. Crosseyed Walter sir I did sir. Wouldn’t trouble only I was expecting some money. Apologise.”

Richie, once the life of the party, has destroyed his health with years of heavy drinking. The same is true for the more charismatic Simon, whose voice we later learn has been damaged by his own alcoholism:

“Seven days in jail, Ben Dollard said, on bread and water. Then you’d sing, Simon, like a garden thrush.”

We know from Stephen’s inner monologue in “Proteus” that Simon disdains his brother-in-law Richie, and it seems that Richie is aware of Simon’s animus towards him; it’s hard to imagine Simon being subtle about such a thing. Despite their mutual antipathy, these two have quite a bit in common. The pair preside over ruined homes and finances. Richie is physically weak, plagued by Bright’s disease, while Simon drinks to numb the grief of his lost wife. Bloom, like Stephen in “Proteus”, describes Richie sending his obsequious son Walter out to beg for the family, while we have just seen Dilly Dedalus selling the family’s possessions to make ends meet while her sisters beg the nuns for dinner in “Wandering Rocks.” Dilly confronted her father Simon for money he claimed not to have, and now we see him drinking that very money away with the boys.

Presumably it’s easier for Bloom to consider the dark fates of his peers rather than his own. Commenting on the song “All is Lost,” Bloom says to Richie, “I know it well.” The double meaning is clear. We know, as does Bloom, that Blazes Boylan is at this very moment jauntily jingling his way north towards Eccles St. unimpeded. Hypothetically, Bloom could have confronted him when their paths crossed in the Ormond, or followed Boylan home, or dropped in unexpectedly. Instead, Bloom has chosen the path of no resistance, and now all hope is lost of disrupting Molly and Boylan’s tryst.

Bloom does his best to repress his thoughts of Molly and Boylan, but Simon Dedalus’ songs are no help. His pals Dollard and Cowley won’t accept “All is Lost” as a substitution for “M’Appari”, demanding simply, “It.” Simon relents, and we readers experience his song in short titbits between long passages of Bloom’s descriptive internal monologue, allowing us to see Bloom gripped by Simon the Siren’s song, note by note. Bowen likens this format to the headlines that characterize “Aeolus,” though in his view the lines of Simon’s song are far more significant. Bloom is “braintipped” with beauty and emotion for the duration of the song, but in the end, this gives him the strength to emerge, as Bowen notes, “the unconquered hero.”

1960’s “Martha”

As mentioned above, “M’Appari” comes from the opera Martha, a pointedly ironic name for Bloom to encounter in this passage (a fact not lost on Bloom). The plot of Martha revolves around two noblewomen who decide to slum it a bit and pretend to be maidservants. They get hired as cleaners by two farmers, and one of them, under the pseudonym “Martha”, falls in love with the farmer Lionel. The women’s plan goes awry as they are totally inept cleaners, and they bolt in the night. Finding that his lady love has suddenly vanished, the lovelorn Lionel sings the aria “M’Appari” lamenting Martha’s absence.

The aria opens with the line, “When first I saw that form endearing…” Richie recognizes Simon’s voice for the first time, while Bloom, like Lionel, is eventually pulled into a bittersweet reverie of the first time he saw Molly’s “form endearing.” Simon’s voice initially soothes and enraptures them, as Simon sings, “Sorrow from me seemed to depart”, the narration reads:

“Good, good to hear: sorrow from them each seemed to from both depart when first they heard. When first they saw, lost Richie Poldy, mercy of beauty, heard from a person wouldn’t expect it in the least, her first merciful lovesoft oftloved word.”

At various points during Simon’s song his listeners merge into a single entity, united by the sound of his voice. Here “lost Richie Poldy” are heartened by the hopeful-yet-sorrowful music and imagery of the aria from the normally sardonic and abrasive Simon. Richie-Poldy is/are still lost, and now they have fallen under the Siren’s spell. While Simon doesn’t intend to lure them onto the rocks or make a throne of their bones, he threatens emotional calamity. He holds their hearts in his palm, whether he knows it or not. Simon’s song leans heavily into sentimentality and nostalgia. If Bloom or Richie were fully ensnared in these traps, it would render them inert and unable to escape their present stagnation of the heart.

As Simon sings of hope (“Full of hope and all delighted…”) Bloom loses his inner composure slightly, tipping into jealous despair, sneering like an incel that “Tenors get women by the score.” The tenor in question is not Simon, of course, but Blazes Boylan, who does seem irresistible to the ladies. Naturally, Bloom is upset that Boylan has enthralled one particular lady with his own jaunty siren song. Bloom’s thoughts roil with Boylan signifiers – the Seaside Girls, the jingles – interrupted first by thoughts of his own epistolary Martha, and then by the horrible image of Molly primping at the hall mirror before she opens the door to Boylan.

The sheer beauty of Simon’s voice pulls Bloom back to the surface. Bloom, grounded once more, wisely concludes there is no reason to envy Simon and considers the hardship of Simon’s life (“Silly man! Could have made oceans of money. Singing wrong words. Wore out his wife: now sings. But hard to tell. Only the two themselves. If he doesn’t break down.”) The siren song still has its grip on Bloom’s mind, melting his thoughts into raw, siren-induced sexuality, dribbling through his mind as horny babble:

“Bloom. Flood of warm jamjam lickitup secretness flowed to flow in music out, in desire, dark to lick flow invading. Tipping her tepping her tapping her topping her. Tup. Pores to dilate dilating. Tup. The joy the feel the warm the. Tup. To pour o’er sluices pouring gushes. Flood, gush, flow, joygush, tupthrob. Now! Language of love.”

Though Bloom’s name opens this passage, we know, as Bloom does, that the one “topping her” this afternoon won’t be him. There is a note of Sweets of Sin in this “flood, gush, flow” of a passage. Buried in all of Bloom’s anguish is the fact that he is a little turned on by Raoul’s dalliances. I think the pain is greater, but Bloom’s heart is conflicted, shall we say. Bloom was momentarily overcome by a similar but slightly more coherent tumble of words as he read select passages from the smutty novel in the bookstall in “Wandering Rocks.” This introduces another reason behind Bloom’s inaction regarding Boylan. He doesn’t totally mind handing his wife “dollar bills” to spend on “the costliest frillies” for “Raoul.” Simon’s song allows Bloom to experience this complex mix of emotions rather than keeping it pent up in his subconscious. Bloom isn’t free of the Sirens yet, though. It’s at this stage that Bloom realizes this aria is from Martha, drawing him towards another Siren, his saucy penpal Martha Clifford. He decides to funnel his arousal into a new sexy letter for her.

As Simon continues his song, the listeners merge together in their musical bliss. Richie and George Lidwell, the lecherous solicitor become one, as do Bloom and Pat the “bothered” waiter:

“How first he saw that form endearing, how sorrow seemed to part, how look, form, word charmed him Gould Lidwell, won Pat Bloom’s heart.”

It's in this moment that Bloom recalls “how he first saw that form endearing,” pulled into a memory of the night he first met Molly at a party at Mat Dillon’s house in Terenure. He recalls falling in love with her all over again, her dress, her eyes, her voice, and how he had the honor of turning the pages as she sang for the party guests. Molly’s song, “Waiting,” was in reality a siren song to lure Bloom. Ironically, Molly is at home waiting at this very moment, though not for him. Molly takes her rightful throne in his memory as “Dolores shedolores,” as the queen of the eastern seas, and the queen of Bloom’s heart.

Bloom feels the immensity of losing Molly to Boylan, merging with the grieving Lionel as Simon’s song crescendoes in its final bars. Bloom sets aside his typically sensible practicality and rapturously likens Simon’s closing notes to a soaring bird, echoing the purple prose of Doughy Dan Dawson that Simon had ruthlessly mocked back in “Aeolus.” Osteen writes that this unflattering juxtaposition falls on Dedalus rather than Bloom, though, insinuating that Simon’s overwrought sentimentality may be the musical version of Dawson’s prose. Lionel’s song ends with him crying out to his lost love:

“—Co-ome, thou lost one!

Co-ome, thou dear one!”

We revisit the theme of the “lost one” once more. The image of the soaring bird and the final extended “Come!” imply the release of orgasm soon to be experienced by Boylan rather than Bloom. Despite this, Bloom’s grief has begun to abate, for the moment anyway. Through the beauty of music, Bloom merges soulfully with Simon and Lionel in the brief amalgam, “Siopold!” Though Lionel sings of loss in “M’Appari,” he gets the girl in the end. Merging with Lionel allows Bloom to dream of his own happy ending and not to be dragged down into the sea by Simon, the Siren of Sentimentality. Bloom has survived the siren’s onslaught and begun to emerge unscathed like Odysseus. Perhaps all is not lost.

Osteen marks Simon as one of the “lost ones,” joining him to his own wife, his beloved Parnell, and “his own departed gentility,” ready to be consumed by the waves once and for all. Unbeknownst to either of them, Simon and Bloom are rivals to become the true father of Stephen Dedalus. Bloom’s ability to recover himself while Simon succumbs once again raises Bloom as the true father figure for Stephen. Simon ironically soothes his rival, giving him the strength to stride forth as the “unconquered hero” and supplant Simon. While Bloom is moved by the beauty of Simon’s song, he is not overcome or carried away entirely. Frank Budgen likened this to Bloom’s steadiness in the face of religious fervor, fundamentally grounded and repulsed by fanaticism of any kind. Hearing Simon’s song allows Bloom to experience the swirl of dark emotions he’s been struggling to tamp down all day. In Osteen’s view, Simon’s song allows Bloom to exorcise his "dejection and jealousy” that arise early in this scene and instead achieve the balance that eludes Simon himself. As Budgen said, “the ear is an organ of balance.” Bloom can now go forth with a greater degree of focus and emotional stability, qualities that will allow him to rescue Stephen later that night. Osteen further points out that, once Simon’s gift is “bestowed” upon Bloom, Simon disappears from the novel altogether, presumably drowning while Bloom floats to freedom and fatherhood.

Further Reading

Bowen, Z. (1974). Musical allusions in the works of James Joyce: Early poetry through Ulysses. Albany: State University of New York Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y9erlwtw

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Green, J. D. (2002). The Sounds of Silence in “Sirens”: Joyce’s Verbal Music of the Mind. James Joyce Quarterly, 39(3), 489–508. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25477896

Kenner, H. (1987). Ulysses. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Laws, C. (2017, May 25). Behind the Song: “M’appari” from Friedrich von Flotow’s Martha - Culturedarm. Culturedarm. https://culturedarm.com/behind-the-song-mappari-friedrich-von-flotow-martha/

REILLY, P. (2019). Love’s Old Sweet Songs: How Music Scores Memory in the “Sirens” and “Penelope” Episodes in Ulysses. Joyce Studies Annual, 74–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26862951

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Schwarz, D. (2004). Reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Palgrave Macmillan.