Ulysses & The Odyssey - Sirens

“A musical episode was easy to place in Dublin, for Dublin is, or was, a musical town, with a particular passion for vocal music. A few Dubliners of the older generation meet in the lounge of the Ormond Hotel and a couple of songs, with an improvisation on the piano, constitute the entertainment. No writer with any respect for probability would dare to make the same thing happen in London.” - Frank Budgen

The Odyssey - Book XII

Circe advises Odysseus on the route to take home to Ithaca, warning him of the Sirens, fearsome creatures who sing beautifully to lure sailors to their island, where they sit enthroned among the bones of all the sailors they’ve eaten. Circe tells Odysseus to have his crew block their ears with wax and to tie him to the mast of the ship. Odysseus will hear the Sirens’ song as they pass the island. If Odysseus asks to be set free, the crew should tie his bonds even tighter until they are well past the island. They do this, and everyone survives.

“Sirens,” Ulysses’ eleventh episode, marks a major stylistic departure from the first ten episodes, evident as soon as the first “Bronze by gold” strikes the opening chords of an abstract and impressionistic overture not remotely parsable for a first-time reader. Frank Budgen recalled that his friend James Joyce enjoyed writing “Sirens” the most out of all the episodes of Ulysses, possibly, he acknowledged, “because the war ended while The Sirens was being written.” As such, Budgen regarded “Sirens” as the “brightest and gayest episode in the whole book.” On the other end of the spectrum, Joyce’s editor Ezra Pound nearly broke out into a cold sweat at the notion of having to edit and eventually sell this new movement of Joyce’s opus, openly questioning Joyce’s judgment. The Artist’s vision won out in the end, but Pound was not the only baffled early reader of “Sirens.” Stuart Gilbert, in his 1930 book Ulysses: A Study, tells how, when Joyce sent an early draft of “Sirens” from Switzerland to England for review, it was held up by the wartime censors, who were convinced it was some kind of code or spy’s cipher. Two professional writers were brought in to examine the arcane document, in the end concluding it was "literature of some eccentric kind.”

Odysseus and the Sirens, c. 475 B.C.E.

The art of “Sirens” is music, hence the aforementioned overture, just like you might hear before the curtain goes up at an opera. Multiple scholars have likened this opening foray to an orchestra tuning before a performance. It includes themes and motifs that will be “heard” in a more robust form later on, foreshadowing the music, both real and metaphorical, that will fill the Ormond Hotel’s bar and restaurant over the course of this episode. If you, like Ezra Pound and the World War I censors, find this overture baffling, re-read it after you’ve read “Sirens” in its entirety. You’ll recognize the various little bits and pieces that permeate the episode as a whole. As always, Ulysses is always best read twice.

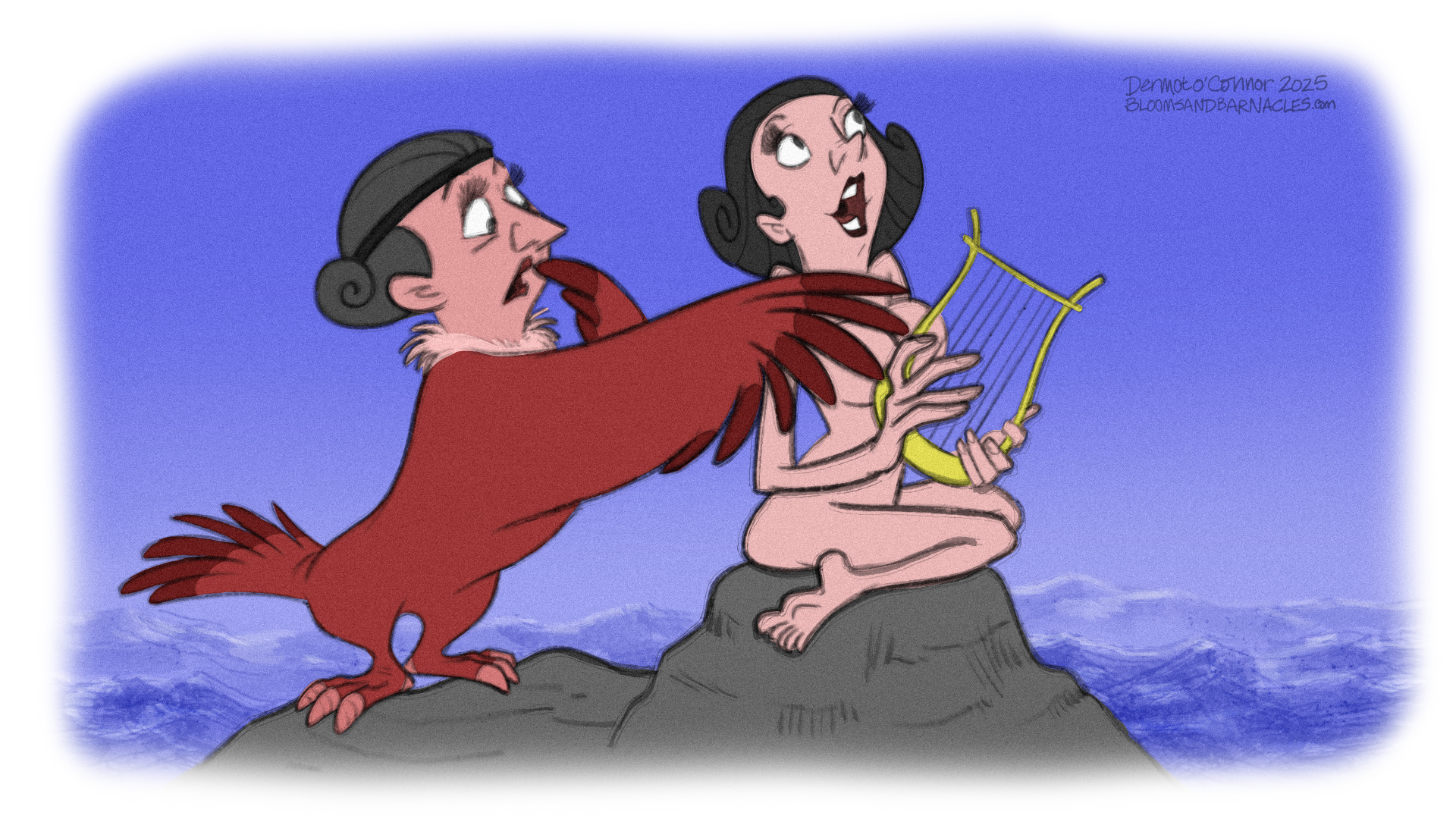

Homer’s Sirens are one of the most iconic monsters of Greek mythology: beautiful women whose song lures unsuspecting sailors to their doom. I was surprised to learn that the Sirens were imagined as birdlike women (and sometimes men!) in antiquity rather than sexy fish-women. In The Odyssey, Homer left the Sirens’ physical form to our imaginations, but they appear explicitly as hybrid bird-humans in the Argonautica. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the depiction of Sirens as mermaids or simply nude women fully supplanted their semi-avian sisters. The change-over was so total that John William Waterhouse’s 1891 painting of the Sirens as birds with women’s heads baffled and disappointed critics, who thought Waterhouse was inaccurately depicting Homer’s famous story, despite the fact that Waterhouse’s painting was inspired by an ancient Greek vase. I personally suspect these critics were just bummed because they didn’t get to see any boobies in Waterhouse’s version. It’s worth pointing out that it’s not so much the Sirens appearance that makes them irresistible in The Odyssey; it’s their voices. Presumably, they could look pretty bizarre or terrifying and still lure men to their doom. This is harder to translate to a painting, ineluctably visible but not especially audible.

Ulysses and the Sirens, John William Waterhouse, 1891

Gilbert writes that “the Homeric correspondences in [“Sirens”] are, generally speaking, rather literal than symbolic.” Homer describes the Sirens “seated in a flowery mead,” and indeed, the tables in the Ormond are decorated with flowers. Joyce’s Sirens of the Liffey are fishy rather than feathery, as we hear about Lydia Douce’s seaside holiday, see a packet of Mermaid brand cigarettes, and hear the ocean inside a seashell. Gilbert also points out that, in the midst of this flowery mead (or meadow), we observe “Blue Bloom is on the rye,” which he believes is a callback to Stephen’s description of Shakespeare overborne in a ryefield (or was it cornfield?) by the vicious Siren Anne Hathaway. The Ormond is also filled with the ineluctable music of the Dublin Sirens, most notably Simon Dedalus and Ben Dollard’s renditions of “M’Appari” and “The Croppy Boy” performed in front of the image of a dusty seascape. Later in “Ithaca,” Bloom describes the scene in the Ormond Hotel as “Shira Shirim,” or Song of Solomon, so even though he is able to pass by the Sirens unscathed like Odysseus, the charge in the air is undeniable.

Ulysses and the Sirens, Herbert James Draper, 1909

The two barmaids, Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy. They are visually alluring, with their bronze and gold hair, their fashionable clothes, and their meticulous skincare. Part of their work is flirting with the customers, as evidenced by the charm they turn on for the patrons but withhold from their male co-workers. These Sirens do not sing however, and they are lured by their male customers rather than doing their own luring. Their personalities resonate strongly in the early pages of this episode, but they fade into the background once the male characters enter the scene. Scholar Richard Ellmann writes in his book Ulysses on the Liffey, “Everyone inspects Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy, the principal sirens of the episode, and everyone is inspected by them, but these young women scarcely exist except as musical motifs.” Blazes Boylan has to cajole Miss Douce to perform her “sonnez la cloche” trick, for instance, and fears no entrapment. She is also so clearly smitten with Blazes, while he only flirts with her out of habit or obligation. She is no different to him than the shopgirl in Thornton’s. Scholar Mark Osteen writes that Boylan exploits the barmaids “without incurring the debtorship of emotional commitments.” He feeds on Miss Douce’s obvious attraction, but never reciprocates. Boylan is more Siren-like in this scenario than either barmaid. Additionally, the barmaid-sirens are not particularly enticing for our Dublin Odysseus. Bloom observes them, but is able to deftly avoid their tepid snares.

Bloom’s attention is diverted by the snares of the unseen Martha. Like the Sirens of The Odyssey, she holds the potential to divert Bloom from his course home unlike any of the other women in this episode. And like the Sirens of The Odyssey, we never actually see Martha. The mere idea of her is enough. Martha poses a danger to Bloom returning to his own private Ithaca, as even an unrequited epistolary affair signals a betrayal that could break Molly’s heart. Bloom’s response to Martha is halfhearted at best, attesting to her mild power as a Siren.

The Sirens and Ulysses, William Etty, 1837

Scholar Jackson Cope believes Molly to be the true Siren of the episode. She is the only actual singing woman in the episode, and it’s her song, “Là Ci Darem,” a song of infidelity and seduction, that draws Boylan into her abode. Of course, thoughts of Molly constantly tug at Bloom, though he does his Odyssean best to repress and avoid them. Gilbert pointed out that the Sirens’ mead was covered in violets and parsley, similar to Calypso’s isle. Molly has already taken on the role of Calypso earlier in the day, and now metamorphoses into a Siren. Cope notes that Gilbert saw Molly as the embodiment of Gaia-Tellus, the Earth Mother, whose symbol was the rose. In the play Helena, Euripides portrayed the Sirens as Gaia’s daughters. Miss Douce wears a rose on her blouse in the Ormond. Though young and beautiful, she hasn’t learned the tricks of seduction mastered by a more mature woman, and therefore, can’t quite ensnare her man. No amount of “sonnez la cloche” will distract Boylan from Molly. The chaste “Idolores” can’t compete with “La Ci Darem,” if you take my meaning. According to Cope, Boylan thus becomes an ironic Odysseus who gives into Molly the Siren’s song willingly and with great gusto. We can imagine a scenario, after the conclusion of the events of Ulysses, where Boylan’s lust for Molly somehow leads to his destruction. He may be the “conquering hero” at the moment, but keep in mind that Bloom is the “unconquered hero” in the text of “Sirens.”

There’s no reason to limit ourselves to female Sirens, either. The Homeric figures that turn up in Ulysses through the works of metempsychosis are often sideways versions of their heroic archetypes. Dublin’s Odysseus is utterly uninterested in the purported Sirens, and the Sirens can’t sing anyway, totally defanging themselves. So why can’t the Sirens also be male? And rather than being ethereally beautiful mermen, why couldn’t they be Simon Dedalus and Ben Dollard? Simon’s rendition of “M’Appari” and Ben’s “Croppy Boy” saturate the hearts of all those in earshot, ineluctably audible and utterly intoxicating. They drown their audience in waves of emotion, recalling deepest love, the horrors of war, gut-wrenching treachery and woozy nostalgia. Unfortunately, their songs and the emotions they provoke are as empty as the seashells on Mr. Deasy’s desk. These twin Siren songs entwine Bloom a bit more than Miss Douce’s garter. In the end, Bloom is conscious of their music’s beguiling quality, criticizing Fr. Bob Cowley’s entrancement:

“Cowley, he stuns himself with it: kind of drunkenness.”

Osteen further elaborates that Simon and Ben themselves are not true Sirens; it’s the sentimentalism permeating their songs that enthralls and destroys their listeners. Their songs appear to bewitch their audience by surfacing such deep emotions, but in reality, the men in the bar are sedating themselves with the shallow nostalgia and patriotism evoked by their performance. The listeners become their own Sirens, pulling themselves beneath the waves with sappy songs and cheap booze, never truly confronting their real emotions and struggles. Osteen writes, “In [Sirens], sentimentalism denotes a moral and economic sophistry that offers bogus or shopworn merchandise as genuine valuables; it is unearned emotional or economic credit.” We know Simon is drowning in grief for his wife, as well as teetering on financial ruin. We’ve observed him in the previous episode, “Wandering Rocks,” cruelly rebuffing his daughter Dilly as she begs him for money to feed the family. Yet in the Ormond, he charms and soothes (and spends the money he denied her). Osteen writes that this current of sentimentalism was foreshadowed in Stephen’s cryptic telegram to Mulligan and Haines:

“The sentimentalist is he who would enjoy without incurring the immense debtorship for a thing done.”

With this in mind, the operatic beauty of music flowing through the Ormond fades and metamorphoses into a din. It’s easy to lose your way in such a cacophony. We need to reset, to get in tune. Joyce told Gilbert that Bloom is this episode’s tuning fork, what Gilbert called the “trustiest of all instruments” who “alone stands for the norm of humanity.” Gilbert further identified Bloom as the conscience of the episode, an Odysseus with his ears open. He is immune to Simon and Ben’s songs, recognizing the signs of enthrallment on Cowley’s face. This is in part because Bloom is sober, but he alone hears Boylan’s song and does not let it lead him astray. Boylan’s jingles become a private Siren song just for Bloom. If Bloom were to follow Boylan’s song or allow it to sway his heart too much, it could lead to genuinely ruinous consequences.

The question of why Bloom doesn’t just pop home during Molly and Boylan’s meeting to sabotage their tryst is a common one. Plausible deniability is on his side – he technically doesn’t know they’re hooking up. What if he decided to come home early, just to pick up the latchkey that he forgot that morning? Most of us would be tempted to quietly put our thumb on the scale in this way if we were in Bloom’s shoes. In “Sirens,” Bloom watches his final opportunity to intervene evaporate before his eyes. Ellmann explained that it is Odysseus’ power to hear the music of the Sirens, but not act on it. His sailors have the power of action but are deaf to the music. Odysseus may appear inert or passive, but only because he is bound to a mast, temporarily restricted in his action. Bloom likewise comes across as passive here, but he is inactive in an Odyssean sense. Boylan’s music tempts him the most but resists this jingly-jangly Siren song nonetheless. Odysseus does not act in this scenario, and so Bloom is also inactive. Ellmann notes that Bloom regains his taste for action in the next episode, “Cyclops.” Lenehan hails Boylan, “See the conquering hero comes.” (And within the hour, he will have). Despite this crushing reality, Bloom is described as the “unconquered hero” in the next paragraph. Odyssean Bloom will not be destroyed by Boylan the Siren.

Further Reading:

Bonollo, M. (2014, June 4). J. W. Waterhouse’s Ulysses and the Sirens: Breaking Tradition and Revealing Fears | NGV. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/j-w-waterhouses-ulysses-and-the-sirens-breaking-tradition-and-revealing-fears-2/

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Cope, J. (1974). Sirens. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (217-242). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/wu2y7mg

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gilbert, S. (1930). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Homer, translated by Palmer., G.H. (1912). The Odyssey. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications.

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Schwarz, D. (2004). Reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Palgrave Macmillan.