Stephen Dynamo

In the thirteenth section of “Wandering Rocks,” Ulysses’ tenth episode, we meet Stephen Dedalus once again, gazing into the window of Old Russell the lapidarist. We last saw Stephen descending the stairs of the National Library with Buck Mulligan in “Scylla and Charybdis,” seeking augury from absentee birds. Mulligan is meeting Haines at the DBC for a mélange and gossip, so Stephen is free once more to indulge in his own overwrought philosophies and fantasies as he wanders the streets:

“Born all in the dark wormy earth, cold specks of fire, evil, lights shining in the darkness. Where fallen archangels flung the stars of their brows. Muddy swinesnouts, hands, root and root, gripe and wrest them.”

Stephen paints a sinister image of humankind’s search for precious gems in the “wormy earth,” the miners transformed into truffle pigs rooting and groping in the darkness, subsumed by their greedy quest. Scholar Daniel Schwarz likens Stephen to Orpheus, descending into the darkness of the Underworld. He argues that Stephen’s infernal imagery contradicts the “present materialistic age” in which he lives, “the darkness of Mammon threatening God’s light.” These lights in the dark are the product of fallen angels, though.

Of course, when Stephen delves beneath the surface, he is not searching for literal silver or rubies. Our literary Orpheus returns to the surface “with the ingredients for literature,” in Schwarz’s words. Schwarz writes that Stephen’s descent, so luxuriously described in these opening paragraphs, is really a descent into the unconscious mind. I, for one, believe Stephen Dedalus’ unconscious mind is far more horrific than any depth of hell. Now swallowed by his Miltonian vision, Stephen must dance the dance of the damned:

“She dances in a foul gloom where gum bums with garlic. A sailorman, rustbearded, sips from a beaker rum and eyes her. A long and seafed silent rut. She dances, capers, wagging her sowish haunches and her hips, on her gross belly flapping a ruby egg.”

This grotesquery reinforces the Joycean notion that the artist’s place is as a conduit for the filth of society. Stephen must plumb the darkest, most lurid depths of the collective unconscious to mine for his “rubies.” Of course, Joyce himself mined the poetry, literature, music, and philosophy of his culture for just the right bits and pieces to work into Ulysses, like a lapidarist seeking just the right cut and shine among jewels. This is not a new concept for Stephen, as he also referred to particularly juicy bits of literature as his “treasures” in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. He acknowledges, with a characteristic dose of self-deprecation, his cultural pilfering:

“And you who wrest old images from the burial earth?”

As with the other sections of “Wandering Rocks,” Stephen’s is interrupted by intrusions describing the simultaneous movements of other Dubliners. Stephen’s thoughts here are interrupted:

“Two old women fresh from their whiff of the briny trudged through Irishtown along London bridge road, one with a sanded tired umbrella, one with a midwife’s bag in which eleven cockles rolled.”

You may recall these two as the women Stephen observes on the strand early in “Proteus.” Spotting the midwife’s bag, at that time, Stephen pondered:

“What has she in the bag? A misbirth with a trailing navelcord, hushed in ruddy wool.”

We see now that their errand on the strand was much more mundane: collecting just short of a dozen cockles. Stephen's imagination spun their time on the shore into a much more tragic and dramatic tableau, a meditation on the creation of life itself, stretching back to the Garden of Eden. They appear here, only for us readers to see, to demonstrate that Stephen’s interpretation of physical reality is far more heightened than it appears to the mere mortals around him. He is in danger of descending into melodrama as much as Hell.

Stephen’s present circumstances grab him by the ankles and force his attention back into stark reality as he carries on down Fleet Street:

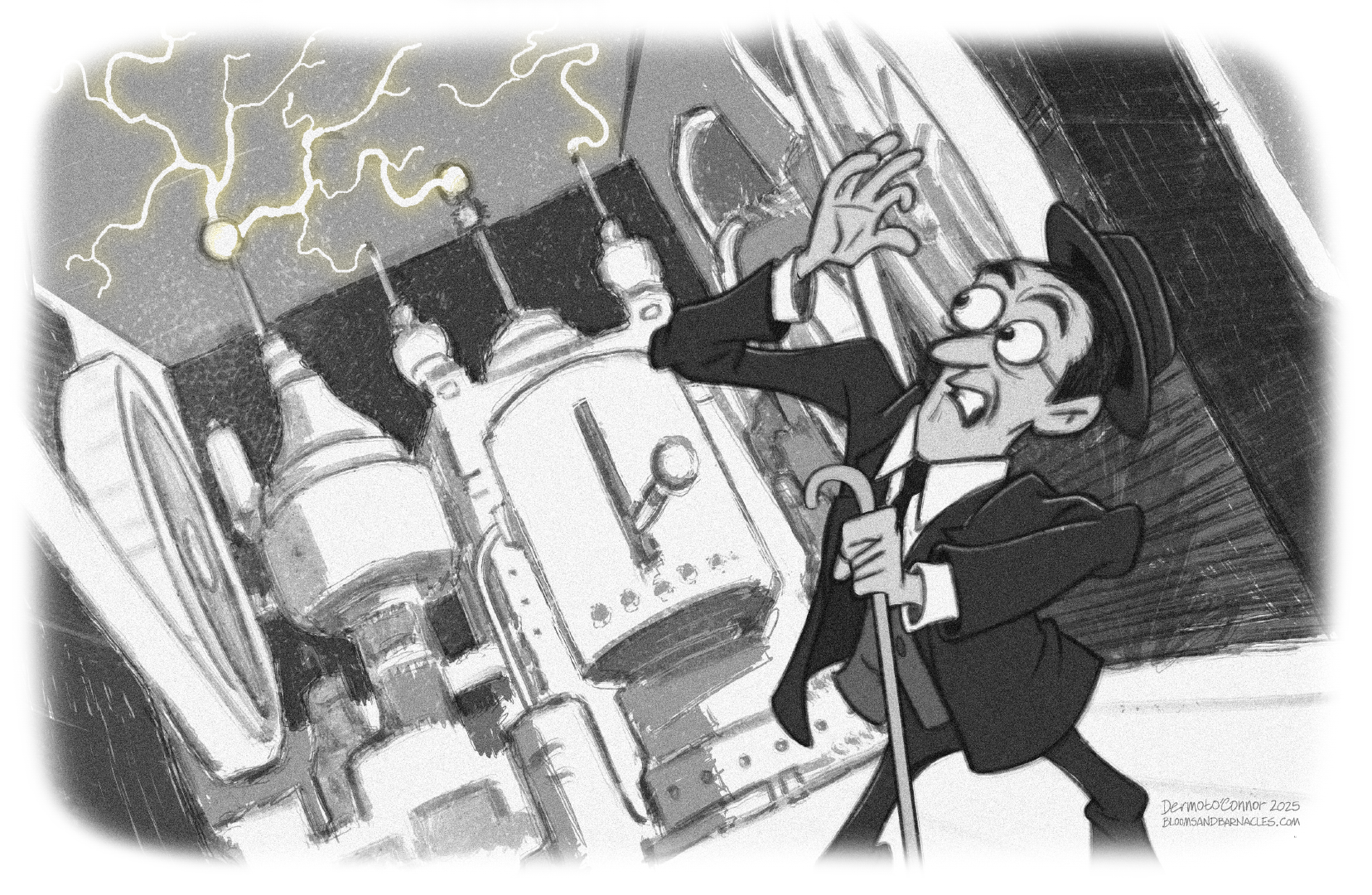

“The whirr of flapping leathern bands and hum of dynamos from the powerhouse urged Stephen to be on. Beingless beings. Stop! Throb always without you and the throb always within. Your heart you sing of. I between them. Where? Between two roaring worlds where they swirl, I. Shatter them, one and both. But stun myself too in the blow. Shatter me you who can. Bawd and butcher were the words. I say! Not yet awhile. A look around.”

Inside the Fleet Street generating station c. 1900

Stephen’s attention is arrested by the din of the Fleet Street generating station, a roaring embodiment of this episode’s art: mechanics. This power station in the city centre powered Dublin’s electric street lights, though it would soon be upstaged by the much larger Pigeon House generating station, which Stephen encountered back in “Proteus”:

“He halted. I have passed the way to aunt Sara’s. Am I not going there? Seems not. No-one about. He turned northeast and crossed the firmer sand towards the Pigeonhouse.”

In “Proteus,” the Pigeon House served as a reminder for Stephen of the dove that symbolizes the Holy Spirit, but the Fleet Street station is haunted by “beingless beings” that “throb” Stephen to his core. Stephen’s sense of foreboding brings to mind Bloom’s description of the Freeman’s Journal printing presses in “Aeolus”:

“Machines. Smash a man to atoms if they got him caught. Rule the world today.”

For Stephen, this power station becomes a representation of the Symplegades, the Wandering Rocks of myth, or more accurately, the Clashing Rocks. Stuart Gilbert described The Symplegades as a blind mechanism, clashing together at regular intervals creating “storms of ruinous fire,” totally indifferent to anyone or anything attempting to pass between them. It’s easy to imagine the enormous dynamos chugging away inside the generating station in a similar fashion. According to Gilbert, Stephen’s fear of the hum of the powerhouse foreshadows his fear of thunder in “Oxen of the Sun.” Such a roar strikes him as otherworldly and overpowering, possibly violent. Gilbert believed Stephen is “scared by his own blasphemy,” as he begs for this numinous, deafening force to spare his mortal life:

“Shatter me you who can. Bawd and butcher were the words. I say! Not yet awhile. A look around.”

Like Jason and the Argonauts, Stephen has no choice but to pass between the Clashing Rocks. Jason released a dove to learn the timing of the Rocks, but Stephen’s dove flew the coop back on Sandymount Strand. Now he must rely on his wits to resolve the tension between his inner and outer worlds. Unfortunately, at this point in the day, Stephen is totally adrift and alone. He copes with the hostile environment around him by slipping into poetic fantasies as he did while looking in the jeweler’s window. The throb within him is out of sync with the throb without:

“Throb always without you and the throb always within. Your heart you sing of. I between them. Where? Between two roaring worlds where they swirl, I. Shatter them, one and both. But stun myself too in the blow.”

To resolve this asynchrony, Stephen must pass between the “two roaring worlds” that buttress this episode: Church and State. Like Jason, he must sail between them at just the right moment and gain his freedom. Stephen lacks Jason’s fortitude, though, and shrinks at such a bold notion:

I between them. Where? Between two roaring worlds where they swirl, I. Shatter them, one and both. But stun myself too in the blow. Shatter me you who can. Bawd and butcher were the words. I say! Not yet awhile. A look around.”

For now, Stephen simply slinks into a side street and gets distracted by a used bookseller:

“I might find here one of my pawned schoolprizes. Stephano Dedalo, alumno optimo, palmam ferenti.”

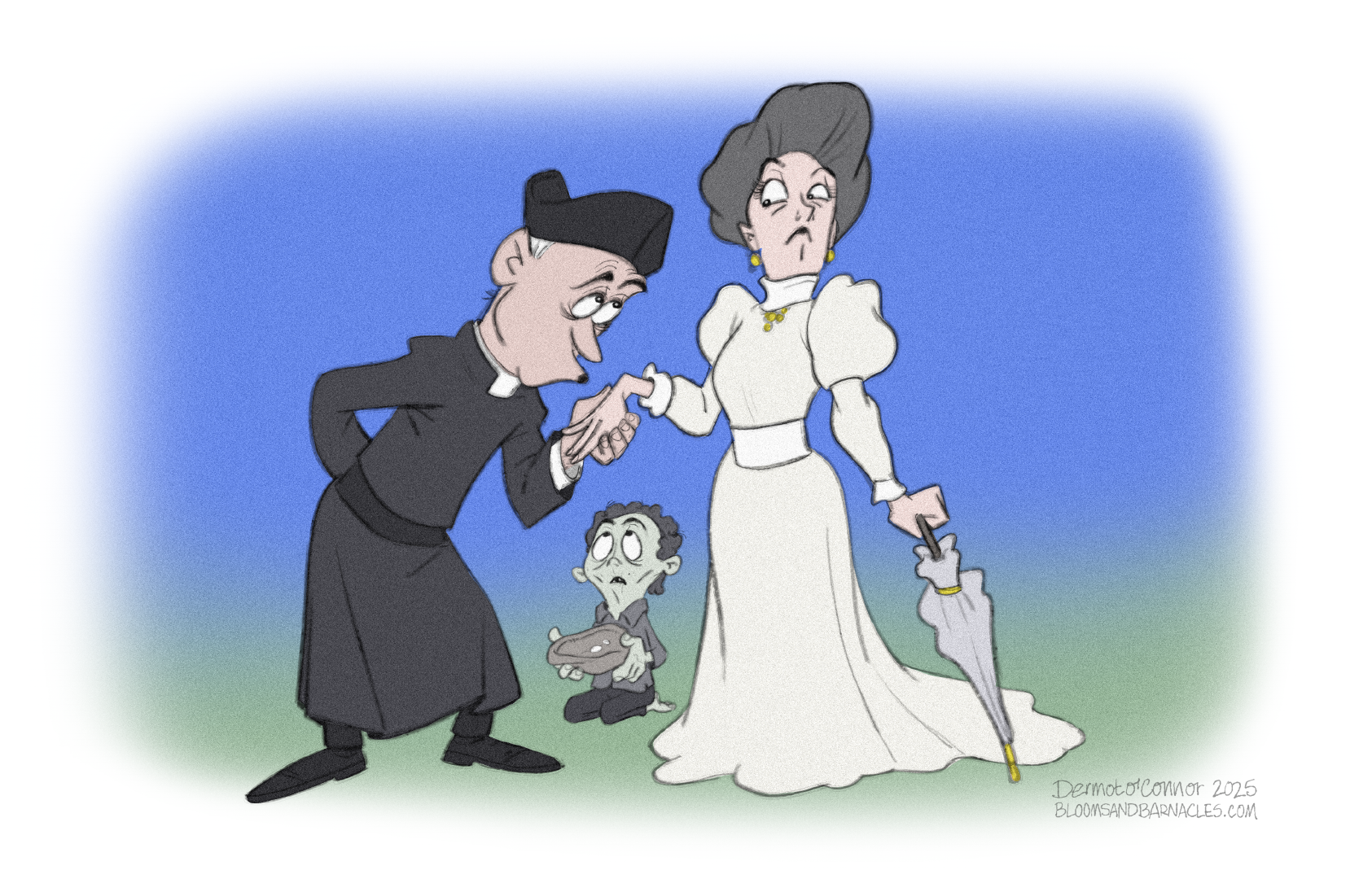

Father Conmee

As he flips through the books, he wonders if he’ll find some of his old books that his sisters have pawned. The Latin inscription means, “To Stephen Dedalus, one of the best alumni, the class prize.” Stephen’s comment here is juxtaposed with a brief sight of Father Conmee making his way through Donnycarney. Could it have been Conmee who wrote this encouraging message to his favorite pupil? Stephen doesn’t linger on the thought, though, as he finds something more intriguing:

“What is this? Eighth and ninth book of Moses. Secret of all secrets. Seal of King David. Thumbed pages: read and read. Who has passed here before me? How to soften chapped hands. Recipe for white wine vinegar. How to win a woman’s love. For me this. Say the following talisman three times with hands folded:

—Se el yilo nebrakada femininum! Amor me solo! Sanktus! Amen.

Who wrote this? Charms and invocations of the most blessed abbot Peter Salanka to all true believers divulged. As good as any other abbot’s charms, as mumbling Joachim’s. Down, baldynoddle, or we’ll wool your wool.”

What arcane volume has Stephen unearthed at this random bookcart? The source for the book that Stephen skims here, The Eighth and Ninth Book of Moses, stumped scholars for decades, particularly because searches for a “most blessed abbot” named Peter Salanka came up empty. Of course, Joyce was quite the polyglot, so scholar Viktor Link expanded his search beyond English-language books. Link found a German copy of The Eighth and Ninth Book of Moses, which he described as a “fantastic pseudoscientific jumble,” and argued this to be the most probable source. It has a chapter on the interpretation of dreams (including dreams about melons and black panthers), a chapter on the language of flowers (including all the flowers that appear in the relevant passage of “Lotus Eaters”), and suggestions on choosing lottery numbers like those in “Ithaca.” Link finds these references alone a bit too vague to be certain that this was a book referenced by Joyce, though.

What really caught Link’s attention was a chapter called “the charms of St. Ignatius” that includes a reference to a Pater Salanka (or Father Salanka in English), indicating a misreading or misspelling that may have crept into Ulysses. The charm Stephen reads here also appears in this book, though it seems to be an amalgamation of several charms from the same section. For example, the words “Sanktus! Amen” are taken from a separate charm, and the word “nebrakada” recurs in various charms in the same chapter. The seal of King David, the cure for chapped hands, and the vinegar recipe are nowhere to be found, but I’m sold on Link’s theory nonetheless. As the book as a whole is nothing too deep or serious, I think we can take Stephen’s aside, “As good as any other abbot’s charms, as mumbling Joachim’s” as a bit of sarcasm or humor. You’ll recall Joachim as the medieval eschatologist whose prophecies Stephen studied in the stagnant bays of Marsh’s Library long, long ago. A sudden question disintegrates Stephen’s silly reverie, “What are you doing here, Stephen?” He’s been discovered.

Stephen is suddenly confronted by his younger sister Dilly, who has had quite a different day than her brother. “Wandering Rocks” presents a stark view of the reality of life for the four Dedalus sisters, who still live at home with Simon. While Brother Stephen has been gallivanting around arguing about Shakespeare in the Library and testing the bounds of perception on Sandymount Strand, they are struggling to find enough to eat. Stephen is paralyzed with fear by the sound of a power station while Dilly has been selling the drapes to buy dinner.

When Stephen and Dilly meet, she is secretly buying a French primer, possibly because she was influenced by Stephen’s stories of his time in Paris. This purchase hints that Dilly shares her brother’s drive to learn and his interest in languages. Does she also possess his brilliance? Dilly clearly demonstrates her resilience and determination – she is willing to educate herself despite all the hardships. She just doesn’t have access to the same elite institutions as her brother, revealing a cruel favoritism within the Dedalus family. No expense was spared on Stephen’s Jesuit education. When the family fell on hard times, the guardian angel Father Conmee made sure Stephen wasn’t left behind. As a result, Stephen is fluent in several languages (we’ve just observed him speaking conversationally in Italian with Almidano Artifoni, quite a rare language to learn in Dublin in this era), while Dilly is scrounging up a few pennies to buy a damaged book from a secondhand cart in an alley to teach herself the basics.

This scene dramatizes the real unequal treatment of sons and daughters in the Joyce household, a divide that Richard Ellmann also described in his biography of Joyce – no expense was spared for James’ education while his sisters were largely neglected. Stephen/Joyce, now grown, feels guilt over this extreme inequity:

“She is drowning. Agenbite. Save her. Agenbite. All against us. She will drown me with her, eyes and hair. Lank coils of seaweed hair around me, my heart, my soul. Salt green death.”

Stephen recognizes that Dilly is drowning, and he can’t save her. He is barely treading water himself. Stephen needs to put on his own life jacket before he can save anyone else, a skill he won’t develop before the end of Bloomsday, as he is too mired in his own despair. Harsh reality has crashed into Stephen once more. Scholar Clive Hart wrote that meeting Dilly is a “more acute reminder than is the violent scene of the assault by Private Carr.”

As blood is the correspondent organ of “Wandering Rocks,” Stephen’s encounter with a blood relative is especially significant. Stephen despairs because he fails his own blood. Even worse, as scholar Mark Osteen points out, this encounter proves that Stephen shares the blood of his consubstantial father, the creeping dread that is never far from Stephen's mind. He sees the pain and suffering his father has caused the family and desperately doesn’t want to recreate it. Osteen writes, “he is trapped between the ties of blood and desire to be bloodless.”

Unlike Stephen, Dilly directly confronts their profligate father, demanding money to support the family. Osteen observes that in “Hades,” Simon sardonically commented that Reuben J. Dodd had paid too much for his son’s life when he tipped his rescuer one florin, but gives his own daughter even less, mere pennies. Stephen, like Simon, has money in his pocket. He could buy the book for his sister and feed the family, but he ultimately chooses not to. Dilly doesn’t know any of this, but Stephen knows all too well. Like father, like son. Like Simon, Stephen has spent a share of his income on booze, and will continue to do so for the remainder of Bloomsday, shirking his duty to his blood kin, who are drowning all around him. His simple statement of “We.” among all the agenbites near the end of this passage indicates not only are both he and Dilly drowning, but both he and Simon are the consubstantial destroyers of the family. The more Stephen resembles his father, the more he becomes the “pale vampire” from his poem. Boody Dedalus’ comment about “our father who are not in heaven” also applies to Stephen in this case. Bloom can provide a better role model of fatherhood, but Stephen hasn’t met him yet. Stephen’s guilt over his inaction reframes his anxiety over artistic creation, his fear of God, and his desire for a magic spell to attract women as petty self-indulgence. Frank Budgen sums up Stephen’s predicament:

“Stephen has a strong sense of family solidarity… he would serve his family if he could. The family bond seems to be the only one of which he recognises the validity. But who would save drowning people must first be a good swimmer.”

It is easy to accuse Stephen of rank selfishness; Schwarz chalks Stephen’s inaction up to immaturity. I agree with Budgen; Stephen is in no position to help himself much less anyone else. I personally see Stephen and Dilly’s situation as a Bucket of Crabs. If you put a single crab into a bucket, it can easily climb out. If you put several crabs into the bucket, they pull one another back down into the bucket and none can escape. Stephen is the crab that made it out. In order for him to rescue his sisters, he has to find stability in the world. It’s still selfish to spend his salary on booze, but giving it all to the sisters keeps him and them in the same poverty trap. One can easily conceive of a situation where Stephen jets off to the continent and leaves them all to suffer. The real-life Joyce escaped the gravity well of Dublin and made his way in Trieste and beyond. He was joined there by a brother and sister in time. Perhaps Stephen can one day pave the way to safety for his sisters, too.

Further Reading:

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gilbert, S. (1930). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Hart, C. (1974). Wandering Rocks. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (181-216). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/wu2y7mg

Hunt, J. (2023). Powerhouse. The Joyce Project. https://www.joyceproject.com/notes/100017powerhouse.htm

Hunt, J. (2023). Throb. The Joyce Project. https://www.joyceproject.com/notes/100016throb.htm

Link, V. (1970). “Ulysses” and the “Eighth and Ninth Book of Moses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 7(3), 199–203. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486837

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Schwarz, D. (2004). Reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Palgrave Macmillan.