Who were the real people in the Ormond Hotel in "Sirens"?

“Sirens,” the eleventh episode of Ulysses, is memorable for its musical prose, but it also stands out as an episode of revelry in the bar and restaurant of the Ormond Hotel. While Bloom cringes in anguish watching Blazes Boylan jingle-jangle off to meet Molly, the other colorful characters drown their sorrows in booze and song. Most of them we’ve met before in one shape or another - “Nuncle Richie” Goulding, Lenehan and of course the dreaded Boylan all cut familiar silhouettes in our imagination. Also featuring prominently are the trio of Simon Dedalus, Ben Dollard, and “Father” Bob Cowley, who we’ve just seen in “Wandering Rocks” discussing Cowley’s plight at the hands of the dastardly landlord Hugh C. Love. Finally, we also meet a few folks who seem to be entirely creatures of the Ormond, including its two barmaids, Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy, and the solicitor George Lidwell.

The Ormond Hotel, conveniently located on Ormond Quay on the north side of the Liffey, acts as the setting of “Sirens.” Scholar Harald Beck wrote a meticulously detailed history of the Ormond Hotel for James Joyce Online Notes, in which he stated very bluntly that:

“There are two principal misconceptions about the setting under which readers of Ulysses may labour. One is that the Ormond hotel presented in the Sirens episode describes the establishment as it existed at No 8 Upper Ormond Quay in 1904; the other is that the derelict premises still standing today at Nos 7 to 11 Upper Ormond Quay at least contain remnants of the hotel Joyce had in mind. Both assumptions are false.”

The Ormond Hotel first opened for business in 1861, though the buildings were first built on the quay much earlier. Beck notes some gaps in the Ormond’s continuity in the 19th century. Its initial run at No. 8 Ormond Quay lasted only a couple years. Thom’s Directory listed various other concerns at that address until the Ormond Hotel re-emerged in 1889. It was next purchased by Mrs. Nora de Massey in 1899, who was the owner in 1904, as reflected in the text of “Sirens”:

“—I’ll complain to Mrs de Massey on you if I hear any more of your impertinent insolence.”

The Ormond Hotel as the real-life Mrs de Massey knew it in 1904 was not the Ormond of Ulysses, however. Beck details in his article how an Ormond Hotel confined to No. 8 alone would have been too narrow to include both the bar and restaurant described in “Sirens.” Mrs de Massey eventually extended the hotel into No. 9, which added room for the restaurant where Bloom and Nuncle Richie eat their dinner, but that wouldn’t happen until late 1905. The restaurant, called The Buffet in real life, would be entirely anachronistic for a scene set in mid-1904.

The Ormond Hotel described in “Sirens” is the hotel as it existed in 1912. In a letter from that year, Joyce mentioned the party wall connecting the bar and restaurant with an opening between No. 8 and No. 9, a feature that wouldn’t have existed in the 1904 iteration of the Ormond but is described in Ulysses. Joyce spent at least one evening in the Ormond with his father and George Lidwell in that year, as well. This is why Joyce chose the Ormond’s bar out of all the bars in Dublin to set “Sirens”; it was a spot where his father spent many evenings singing and carousing, often in the company of his friend Lidwell. This is just the scene we observe in “Sirens.”

To address the second claim made by Beck, the Ormond was extensively remodeled and rebranded as the New Ormond Hotel in 1933. Frank Budgen lamented at the time:

“The bar of the Ormond Hotel, where the actors of the drama enter and through which they leave, exists as it did in 1904, but the rest of the space – saloon in which Simon Dedalus sang and dining-room in which Bloom and Richie Goulding listened and ate – has disappeared in the rebuilding and reorganising of the Ormond as the New Ormond Hotel.”

On a similar and succinct note, Beck also quotes from the January 2, 1933 edition of the Irish Times:

“[The new Ormond] now reconstructed beyond recognition.”

The 20th century Ormond Hotel eventually stretched from No. 7 to No. 11 Ormond Quay, dominating the riverside. The hotel closed for good in 2006 and has stood derelict ever since, its tattered awnings still advertising the defunct Sirens Bar for more than a decade. The discs declaring its landmark status had been prised from the facade at some point, leaving crusty brown circles as reminders of brighter days long gone. Planning permission was denied in 2014 to replace the derelict Ormond with a six story luxury hotel on the grounds that such a structure would overpower the visual character of Ormond Quay. Another developer purchased the property in the 2010’s and demolished the Ormond in 2018, leaving instead a gap-toothed appearance to the quay’s Georgian face. The site remains in this condition as of this writing in November 2025.

Regardless of the nightmare of recent history, the faux Ormond of 1904 reigns eternal, along with its denizens, except for poor George Lidwell. He is such a forgettable Ulysses character, in fact, that not only did I forget about him entirely until my recent re-read of “Sirens” in preparation for writing this blog post, but he does not appear on otherwise comprehensive lists of Ulysses characters on both Wikipedia and The Joyce Project. He appears as a tipsy solicitor who flirts with the barmaids and listens to the ocean inside Lydia Douce’s seashell. Allowing Lidwell to fade from memory is a mistake, though, because in real life he played a significant role in Joyce’s struggle to get Dubliners published.

The Dubliners publishing hell that Joyce endured is too long a story to tell in detail here, so we’ll just focus on Lidwell’s role. Dubliners was in jeopardy in 1911 because the publisher, Maunsell and Co., deemed its contents potentially libelous and refused to move forward unless Joyce removed the offending content. In a classic example of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object, Joyce refused to budge. Joyce sought legal representation to compel Maunsell to make good on their end of the publishing deal. He ended up hiring his father’s counsel, George Lidwell, though as it turns out, Lidwell was a terrible choice as he mainly worked in police courts and knew nothing about literature, art, or the publishing business.

Rather than put pressure on the publisher, Lidwell was sympathetic to their position, writing a letter that stated that while the contents of Dubliners were indeed offensive, they probably wouldn’t be libelous enough to incur a lawsuit. Joyce was understandably irate and demanded an immediate meeting with Lidwell. Richard Ellmann, in his biography of Joyce, quotes a letter from Joyce to his brother Stanislaus recounting how he “sat for an hour on a sofa in Lidwell’s office, and considered buying a revolver to ‘put daylight into [his] publisher.” Lidwell was nowhere to be found. Knowing that the Ormond was a frequent haunt of Lidwell’s, Joyce staked out the hotel bar until the runaway solicitor got thirsty. Ellmann recounts how Joyce and Lidwell spent an hour heatedly arguing before Joyce persuaded him to write a better letter. Joyce repaid Lidwell’s contribution by immortalizing him as a drunken lecher in Ulysses, a solicitor who only solicits barmaids. For whatever reason, the infamy doesn’t seem to have stuck to ol’ Lidwell, so he can rest easier in the afterlife than, say, Reuben J. Dodd.

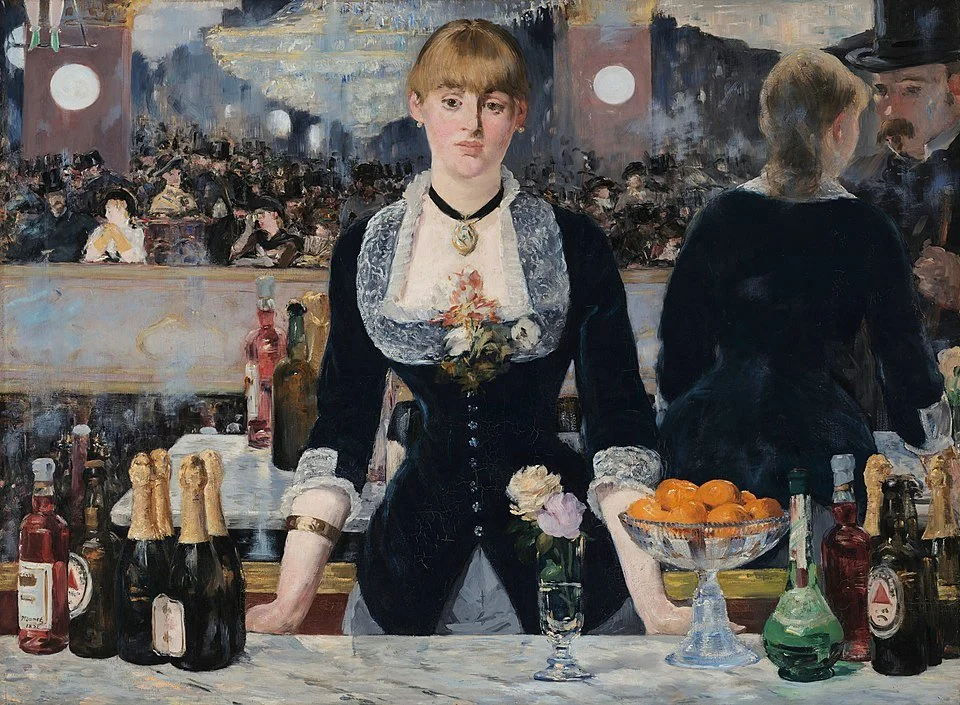

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Édouard Manet, 1882

Finally, let us consider the barmaids, Miss Lydia Douce and Miss Mina Kennedy. According to scholar John Simpson, they are based on workers from an entirely different Dublin boosing shed, the Bailey in Duke St. The Bailey is still around today, just up the street from Davy Byrne’s moral pub, and was a famous haunt for writers in the 20th century. Because of its literary clientele, the Bailey was also the long-time home to a piece of a different demolished Ulysses landmark – the door of 7 Eccles St., until it was moved to its current home at the James Joyce Centre. Simpson, referring to work by scholar Luca Crispi, explains that “Sirens” was extensively rewritten by Joyce. In the original version, both barmaids were described as having bronze hair, rather than one bronze and one gold, and Lydia’s surname was “Douse.” This is the clue that connects us to the Bailey.

Simpson cites a 1945 article by Dubliner James Meagher in which he reminisces about life in the city in the 1920’s, recalling, “incidentally while I was a customer Miss Douse of the golden hair the Ormond Hotel barmaid of the ‘Sirens’ was the manageress of the 'Bailey.'” Census records back up the assertion that the “manageress” of the Bailey was named Dowse. Alice Dowse, one of three Dowse sisters who worked at the Bailey, became the proprietor in 1894. Her sister Maggie was listed as manageress in the 1901 census. Simpson argues it would have been a third sister, Ellen, that Meagher recalls meeting, as Maggie died in 1908. Ellen got promoted from cashier to manageress and served in that role for many years. It’s not known why Joyce chose the name Lydia. As for Miss Kennedy, Simpson reports that a Mary Kennedy is listed in the 1901 and 1911 censuses as the Bailey’s housekeeper.

Further Reading:

Beck, H. (2021, Sep 26) Joyce’s Ormond Hotel. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-environs/ormond

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Simpson, J. (2021, Sep 20). Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy at a different bar. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/miss-douce