A POLISHED PERIOD

“—He spoke on the law of evidence, J. J. O’Molloy said, of Roman justice as contrasted with the earlier Mosaic code, the lex talionis. And he cited the Moses of Michelangelo in the vatican.”

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

In Ulysses’ seventh episode, “Aeolus”, Evening Telegraph editor Myles Crawford has challenged the assembled men in the newsroom to name any man the equal of Dublin’s journalistic legend, Ignatius Gallaher. He now makes a similar challenge concerning Dublin’s lawyers:

“—They’re only in the hook and eye department, Myles Crawford said. Psha! Press and the bar! Where have you a man now at the bar like those fellows, like Whiteside, like Isaac Butt, like silvertongued O’Hagan. Eh? Ah, bloody nonsense. Psha! Only in the halfpenny place.”

As Stephen Dedalus silently buries himself in rhyme scheme, one man steps forth, brave enough to answer Crawford’s demands - J. J. O’Molloy. The disgraced attorney suggests the improbably named Seymour Bushe, K.C.:

“—One of the most polished periods I think I ever listened to in my life fell from the lips of Seymour Bushe. It was in that case of fratricide, the Childs murder case. Bushe defended him.”

We’re given no context for the Childs murder case, but that’s because the men in the newsroom would already be familiar with it. We’ll get to who Bushe was, the Childs murder case, and his courtroom speechifying in a moment, but let’s first take a moment to consider the art of rhetoric, the corresponding art of “Aeolus”. O’Molloy presents a fragment of Bushe’s famously eloquent defense, the second bit of rhetoric analyzed by the gathered newsmen, keeping with the structure of a classical rhetorical treatise:

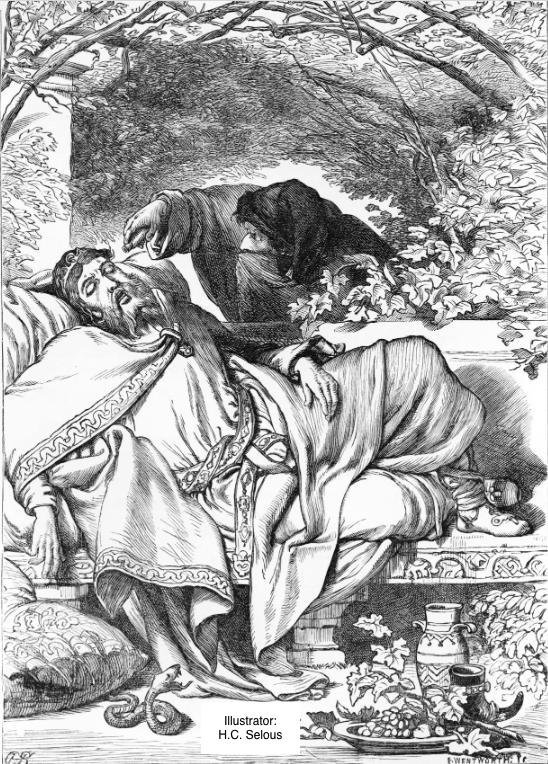

“J. J. O’Molloy resumed, moulding his words:

—He said of it: that stony effigy in frozen music, horned and terrible, of the human form divine, that eternal symbol of wisdom and of prophecy which, if aught that the imagination or the hand of sculptor has wrought in marble of soultransfigured and of soultransfiguring deserves to live, deserves to live.

His slim hand with a wave graced echo and fall.”

Bushe’s oratory is certainly better received than the exhausting purple prose of Doughy Dan Dawson; it even moves the heart of Stephen Dedalus, who blushes, “his blood wooed by grace of language and gesture.” Bushe’s defense is an example of forensic speech, one of three rhetorical styles described in Aristotle’s Rhetoric. Forensic rhetoric was usually demonstrated through legal argument, just as O’Molloy does here. O’Molloy’s recitation of Bushe’s defense also demonstrates the oratorical skill of memoria, the necessity of a speaker to have a strong memory. Of course, we see O’Molloy recalling Bushe’s defense, but Joyce is relying on his own memoria here as well, since he was present for the real Bushe’s defense as a young man.

This is also where things start to go awry. As O’Molloy begins to demonstrate his prowess for memoria, he almost immediately stumbles on a detail, proving him to be an unreliable rememberer:

“—He spoke on the law of evidence, J. J. O’Molloy said, of Roman justice as contrasted with the earlier Mosaic code, the lex talionis. And he cited the Moses of Michelangelo in the vatican.”

Michelangelo’s Moses in San Pietro in Vincoli

O’Molloy recalls Bushe throwing back to Moses and the Romans in order to demonstrate the ancient precedent of the law of evidence, referencing quite eloquently Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses in the Vatican, “that stony effigy in frozen music, horned and terrible, of the human form divine…” etc., etc. However, Michelangelo’s Moses is not in the Vatican, but rather in Rome in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, a sort of cultural canary in the coal mine for those who can see it. Cracks appear in O’Molloy’s memoria.

Adrian Hardiman, former Irish Supreme Court judge and author of the fantastic book Joyce in Court, wrote that Joyce used court cases in his work not necessarily to present the hard, objective facts of a historic legal case, but instead “to question what can be truly known about any past event, or about the human motivation that lay behind it.” It is Hardiman’s contention that Joyce used flawed but popular narratives about history to show how history is remembered amongst ordinary people. We’ve seen this technique portrayed through characters like Mr. Deasy and Myles Crawford. O’Molloy’s legal analysis offers just one more flawed perspective, and his mistake about Michelangelo’s Moses is only the tip of the iceberg.

Let’s begin by examining the Childs murder case. As O’Molloy states, this was a famous case of fratricide, one brother killing another. The brothers in question were Samuel and Thomas Childs. Thomas was an elderly miser who lived alone in 5 Bengal Terrace near Glasnevin Cemetery. Hardiman notes that Thomas was a bit peculiar in that he “transacted his own domestic business,” meaning he made his own tea and fluffed his own pillows rather than employing a domestic servant. In September 1899, when Thomas was found bludgeoned to death with his own fire irons, suspicions turned to his brother, Samuel.

Indeed, Samuel had fallen on hard times. He had retired from his career as an accountant, but his paltry pension wasn’t enough to support himself, his wife and their children. Records showed Samuel had taken small loans from Thomas in the past, and he had been seen around Thomas’ neighborhood on the night of the murder. When police scoured Thomas’ home following his murder, they found a copy of his will naming Samuel as the primary beneficiary, adding to the money motive. Most damning of all was the fact that there was no sign of a break in. Police investigators determined the cobweb-covered, double-bolted back door hadn’t been opened in years, hermetically sealed, they said. The only keyholder to the front door, apart from Thomas, was Samuel, demonstrating opportunity. A few days after the murder, Samuel said to a constable he met at Dunphy’s Corner, “Suspicion points to me. O, that unfortunate latchkey,” which only increased police suspicion against him. The Crown’s case, though largely circumstantial, was considered strong at the time. Samuel’s goose was surely cooked.

The former 6 & 5 Bengal Terrace, August 2022

Upon scrutiny, however, the Crown’s case against Samuel disintegrated. Samuel Childs was defended by Seymour Bushe as well as Tim Healy, who in reality carried the defense rather than Bushe. The defense was able to demonstrate that while Samuel had borrowed some small loans from his brother, Samuel was in truth Thomas’ creditor. The older brother had borrowed quite a bit of money from the younger, and the loan had yet to be repaid in full.

The real bombshell, though, was a cold kettle full of water sitting on top of cooled ashes in Thomas’ fireplace. The Crown had insisted that the back door of Thomas’ residence couldn’t possibly have been opened anytime in recent memory. They had even built a scale model of Thomas’ house that left out the back door because they found it so inconsequential. Neighbors testified that Thomas would have needed to go outside through the back door to collect water or use the jakes as the houses in Bengal Terrace lacked running water. The kettle in the fire proved that he had gone out that very night for water, opening the door (literally) to the possibility that someone could have forced an entry without breaking and entering. Add to this the fact that Thomas had asked for police protection against “corner boys” he had seen malingering in the laneway behind his house, a detail conveniently left out of the prosecution's case. The prosecution collapsed, the house model was withdrawn from evidence, and Samuel Childs was acquitted in the end, thanks mainly to the keen defense of Healy.

As an epilogue, Hardiman pointed out that Childs’ acquittal rested on a lack of evidence, as guilt could not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. However, Childs was proven merely “not guilty” rather than innocent. It remains peculiar that nothing of value was stolen from the house, including cash. Surely the corner boys would have made away with such valuables. It’s also reasonable to think that an argument about money could have arisen and turned ugly, no matter the financial status of either party. In any case, Samuel Childs escaped the gallows.

The courthouse in Green St., Dublin, where Childs was tried

The Childs murder case was quite a scandal in its day. Murder, outside of political assassination, was exceedingly rare in Victorian-era Dublin. A middle-class murder made for even better gossip, and as Hardiman wrote, “There cannot have been so middle-class a murder [trial] as that of Samuel Childs.” The Childs were a respectable, Protestant family that had come apart at the seams. The Childs’ brothers’ father had once been the carver and gilder to the lord lieutenant. Samuel Childs was a churchgoer, and a third deceased brother was a well-known clergyman of the Church of Ireland, showing the hypocrisy of the family’s Christian morals. A scandal amongst the Protestant middle class provided “incentive of voyeurism for the Catholic majority,” according to Hardiman.

The case’s inclusion in Ulysses proves the truth of these notions. Despite the passage of five years, the Childs murder trial is still worthy of note to the various Dubliners we meet on June sixteenth. In “Hades”, as Paddy Dignam’s funeral cortège passes Bengal Terrace on the way to Glasnevin Cemetery, the murder house is noted:

“Mr Power pointed.

—That is where Childs was murdered, he said. The last house.

—So it is, Mr Dedalus said. A gruesome case. Seymour Bushe got him off. Murdered his brother. Or so they said.

—The crown had no evidence, Mr Power said.

—Only circumstantial, Martin Cunningham added. That’s the maxim of the law. Better for ninetynine guilty to escape than for one innocent person to be wrongfully condemned.”

The topic of the Childs murder case is even taken up by the medical students gathered together in “Oxen of the Sun”:

“... the fratricidal case known as the Childs Murder and rendered memorable by the impassioned plea of Mr Advocate Bushe which secured the acquittal of the wrongfully accused…”

For our purposes as Joyce readers, there are several connections to our favorite author that make this case all the more tantalizing. First, as mentioned previously, the Childs trial was attended by a 17-year-old James Joyce. His father had encouraged him at one stage to study law, and although a Joycean law career never materialized, his interest in the law remained. The Childs trial was a major sensation in its day, and Joyce was only able to find a seat in the packed courtroom due to a family connection that guaranteed him a spot for all three days of the trial. Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann pointed out as well that Thomas Childs stated in his will that six volumes of his poetry were to be published by the estate and submitted to the library at Trinity College. Perhaps a young Joyce got wind of this and made a similar request of his brother Stanislaus two years later, inspiring Stephen’s request in “Proteus”:

“Remember your epiphanies written on green oval leaves, deeply deep, copies to be sent if you died to all the great libraries of the world, including Alexandria?”

Second, Alexander Keyes (yes, that Alexander Keyes) was on Childs’ jury. It’s unclear if Joyce knew about this, as Keyes’ jury duty is not mentioned in Ulysses, despite Keyes playing such a prominent role in an episode where Bushe and Childs are also a focus. Perhaps Joyce felt it was just too much to include, or perhaps he just didn’t know. However, there is something thematically satisfying about Keyes deciding the fate of a man who was accused of murder due to his status as a keyholder.

Finally, a Joyce family member lived next door to Thomas Childs. Josephine Murray, née Giltrap, appears in Ulysses as Aunt Sara, wife of nuncle Richie Goulding, who Stephen decided not to visit in “Proteus”. In real life, Aunt Josephine was a major supporter of Joyce’s writing once he had moved to the Continent. Aunt Josephine’s father, James Giltrap, had died the day before the Childs murder, so James Joyce and his father John would have attended his funeral in 6 Bengal Terrace while the police were combing 5 Bengal Terrace for evidence. Consistent with the various minutiae our Dubliners mistake, 5 Bengal Terrace is the second to last on the row, not the last as Mr. Power stated in “Hades.”

Another lingering question about the Childs murder trial - why does O’Molloy center Bushe’s defense rather than Tim Healy’s? Is it merely more faulty memoria? As it turns out, Healy’s omission is purposeful, but on Joyce’s part rather than O’Molloy’s. Healy was a leading opponent of Charles Stewart Parnell at the time of the latter’s political downfall. The Joyce family were staunch Parnellites, and the legend goes that 9-year-old Joyce wrote a poem entitled “Et Tu, Healy?” which decried Healy’s role in Parnell’s downfall. John Joyce had it printed and distributed amongst family and friends, though only the final three lines are known today:

Tim Healy, ca. 1900

“is quaint-perched aerie on the crags of Time

Where the rude din of this century

Can trouble him no more.”

The lines, like O’Molloy’s recitation of Bushe’s defense, are a product of memoria, as they are recalled in Stanislaus Joyce’s biography of his older brother, My Brother’s Keeper. In any case, James Joyce carried a grudge against Healy great enough to write him out of Childs’ defense and make Bushe the star attorney. The newsmen are aware of Tim Healy, as Crawford mentions Healy by name in the headlined passage, A MAN OF HIGH MORALE, directly following the passage (A POLISHED PERIOD) in which Bushe is quoted. Crawford describes Healy as “a sweet thing… in a child’s frock,” the implication being that Healy was too naïve and facile to be morally motivated in his opposition to Parnell. It’s clear that Healy is omitted from Childs’ acquittal intentionally.

Bushe had at least one thing in common with Parnell - his career was interrupted by a divorce scandal. MacHugh alludes to this in “Aeolus”:

“—He would have been on the bench long ago, the professor said, only for .... But no matter.”

Like Parnell, Bushe carried on a secret affair that was revealed when his partner divorced her husband and then subsequently married Bushe. At least according to MacHugh, this cost Bushe a judgeship. In 1904, Bushe moved from Dublin to London, presumably to escape this scandal, where he became King’s Counsel, which is why O’Molloy refers to him as Bushe K.C.

And what of Bushe’s eloquence? He was well-regarded, famed for his “exalted forensic eloquence,” so sayeth Adrian Hardiman. Though Bushe contributed to Childs’ defense, there is no record apart from Joyce’s memoria that he cited either Roman or Mosaic law in court, or that he spoke of lex talionis, or retributive law, taking an eye for an eye. He did speak on the law of evidence, but not in the way implied in J.J. O’Molloy’s recitation. Bushe was fairly liberal for his time, believing in women’s suffrage in particular. In the Childs case, Samuel’s wife was not allowed to testify on behalf of her husband, allowing him an alibi for the night of the murder. At the time, women’s testimony was not accepted in Ireland, though it was accepted in Britain. Bushe argued in court that Mrs. Childs’ testimony should be permissible as evidence on these grounds.

And in the porches of mine ear did pour.

Richard Ellmann, in Ulysses of the Liffey, takes aim at Bushe’s supposed eloquence. Though Bushe’s quoted words are enough to woo Stephen’s blood “by grace of language and gesture,” they don’t contain much substance. Stephen, in turn, quotes from Hamlet as O’Molloy begins his recitation: “And in the porches of mine ear did pour.” The poison being poured in Stephen’s ear is this empty rhetoric, so hallowed in the memory of O’Molloy, but ultimately signifying nothing. Or, as Ellmann put it, “Its fustian is marked by ostentatious pairings of phrases long since drained of meaning,” and that it “makes petrified absurdities of gods and men.”

We may be swayed at first because we are presented with Bushe’s rhetoric as an example of beautiful speech rather than as an object of mockery like Dan Dawson’s speech, but we don’t really learn anything about any of the topics that O’Molloy recalls Bushe speaking on. O’Molloy may be on more solid ground than Crawford with his stories of the Invincibles or the North Cork Militia, but the rhetoric is ultimately hollow and inexact - one more warning that we “mustn’t be led away by… sounds of words.”

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gekoski, R. (2013, Apr 20). A ghost story: James Joyce’s lost poem. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/a-ghost-story-james-joyce-s-lost-poem-1.1363055

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Hardiman, A. (2006, Jun 10). How Joyce took on the law. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/how-joyce-took-on-the-law-1.1015069

Hardiman, A. (2017). Joyce in court. Head of Zeus.

Hodgart, M.J.C. (1974). Aeolus. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (115-130). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yy2gpfhs

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Joyce, S. (1958). My brother’s keeper: James Joyce’s early years. New York: The Viking Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yra2d3xd

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Thornton, W. (1968). Allusions in Ulysses: An annotated list. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/ucwq3x7

Tompkins, P. (1968). James Joyce and the Enthymeme: The Seventh Episode of “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 5(3), 199–205. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486701