Decoding Dedalus: RHYMES AND REASONS

“That is how poets write, the similar sounds. But then Shakespeare has no rhymes: blank verse. The flow of the language it is. The thoughts. Solemn.” - Leopold Bloom

This is a post in a series called Decoding Dedalus where I take a passage of Ulysses and break it down line by line.

The passage below comes from “Aeolus,” the seventh episode of Ulysses. It appears on page 138 in my copy (1990 Vintage International). We’ll be looking at the passage headlined “RHYMES AND REASONS.”

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

Stephen Dedalus once again finds himself ensnared in the nets of crusty old men in “Aeolus,” Ulysses’ seventh episode. Rather than Mr. Deasy’s rants on Unionism and antisemitism, Stephen is now stuck listening to Evening Telegraph editor Myles Crawford’s semi-factual tales of Irish nationalist history. Stephen has dropped by the newspaper’s office to deliver Mr. Deasy’s letter on foot and mouth disease for publication. While the older men encourage Stephen’s writerly gifts, they offer the young artist no true wisdom. As per usual, Stephen loses himself in an intellectual reverie amidst their banter in a section headlined RHYMES AND REASONS.

Let’s take a look, line by line:

“Mouth, south. Is the mouth south someway? Or the south a mouth? Must be some. South, pout, out, shout, drouth.

Back on Sandymount Strand, Stephen had torn a corner from Deasy’s letter to scribble a few lines of his vampire poem. Crawford notices the paper is torn and suspects Deasy’s trademark temper:

“—That old pelters, the editor said. Who tore it? Was he short taken?”

Of course Stephen knows better. Crawford soon loses himself in his own daydream - of the long-gone glory days of Mr. Ignatius Gallaher, pressman extraordinaire. For Stephen, history is a nightmare from which he cannot awaken, and it continues to plague him even here, the office of an organization dedicated to writing about the present. Crawford’s denunciation of some “bloody nonsense,” combined with his twitching mouth, conjures the vampire in the young poet’s mind. Scholar Zack Bowen describes Stephen’s retreat into his own mind as a “satiric defense mechanism to protect himself against involvement with other people, living and dead.” Nightmare of history got you down, Stephen? Why not silently tinker with your vampire poem to pass the time and soothe your jangled nerves?

We explored in a previous post how James Joyce (and by extension, Stephen Dedalus) cribbed bits of this poem from Douglas Hyde’s translation of a traditional Irish song, “My Grief on the Sea.” The final stanza of Hyde’s translation reads:

“And my love came from behind me -

He came from the South;

His breast to my bosom,

His mouth to my mouth.”

“My Grief on the Sea,” which appears in Love Songs of Connacht, is written in the style of a ballad and employs a fairly simple rhyme scheme, as you can see in this stanza. Scholar Robert Adams Day wrote that Joyce is deliberately depicting Stephen revising Hyde’s poem, particularly his rhyme scheme, as a subtle critique of what Joyce saw as poor verse. What does “he came from the South” even mean? Why is it necessary to know the cardinal direction of her love, who is a ghostly apparition embracing his still-living lover from beyond the veil of death? Hyde translated the poem from Irish, and the original verse is closer to:

“My lover came to my side

Shoulder to shoulder,

And mouth to mouth.”

Douglas Hyde

The inclusion of the ghostly lover’s southerly approach is Hyde’s invention, purely for the sake of rhyme. In President Hyde’s defense, there is a drouth of words that rhyme with “mouth.” Of course, in the context of “mouth,” “south” can take on a sexual connotation. Think back to “Lotus Eaters” when Bloom realizes his fly is down in church, and he thinks, “Good job it wasn’t further south.” You get the idea. I doubt Hyde had this in mind when he was talking about a mouth in the south, but I think it’s reasonable to assume it gave Joyce a chuckle to have Stephen ponder, “Is the mouth south someway?”

Beyond the dirty joke, the meaninglessness of the mouth-south rhyme remains problematic. Notice how Stephen tries to find a meaningful connection between mouth and south, but ultimately can’t find one and continues to search for a different rhyme. He wants a reason for his rhyme (get it?). Perhaps Stephen can find inspiration in Professor MacHugh, the lurking vampire of the office, who creeps up behind Stephen:

“—Good day, Stephen, the professor said, coming to peer over their shoulders. Foot and mouth? Are you turned...?”

A sick Joycean burn on the Professor. Whether or not he approaches from the south is unknown to scholarship.

Mouths in Ulysses do carry some significance. They are often tied to voice and breath, and thus to life and to expression through speech. We see this first as Stephen manipulates the proto-speech of celestial bodies and terrestrial waves into the speech of humans, produced by a mouth, back in “Proteus”:

“His lips lipped and mouthed fleshless lips of air: mouth to her moomb. Oomb, allwombing tomb. His mouth moulded issuing breath, unspeeched: ooeeehah: roar of cataractic planets…”

And:

“Listen: a fourworded wavespeech: seesoo, hrss, rsseeiss, ooos. Vehement breath of waters amid seasnakes, rearing horses, rocks.”

Notice the presence of breath both in Stephen’s wordless rhyming and in the roaring waters. In this early stage, he called upon the elements to give shape to his words. Now that his poem is in a more refined stage, the mouth imagery must take on deeper meaning.

“Rhymes: two men dressed the same, looking the same, two by two.”

Stephen likens his clunky rhyme scheme to “two men dressed the same, looking the same, two by two.” (We’ll explore this in more depth momentarily.) The image of two men, appearing so similar, call to mind the consubstantiality that so unnerved Stephen in his earlier episodes. In “Proteus”, for instance, Stephen fretted over being “made not begotten” by “the man with my voice and my eyes,” adding a few lines later, “My consubstantial father’s voice.” If we take Stephen and his father as the two men dressed the same, we see that Stephen’s voice is constrained by his inherited consubstantiality. Another cul de sac of wisdom. To be free of his “consubstantial father’s voice,” Stephen must kindle his own poetry with his own breath.

Having written himself into a corner, Stephen reaches for one of the poetic greats for inspiration:

“........................ la tua pace

.................. che parlar ti piace

Mentre che il vento, come fa, si tace.”

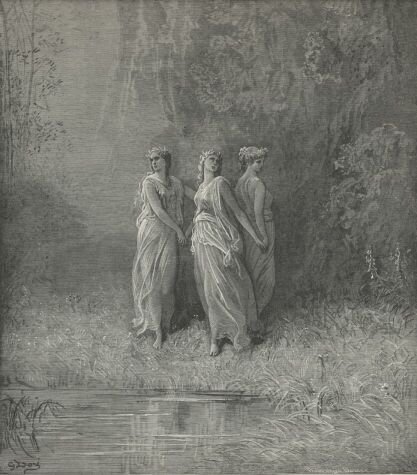

Dante Alighieri, Gustave Doré, 1860’s

It’s easy to be thrown by this truncated intrusion written in fragments of Italian whether you are a first time reader of Ulysses or an old pro. The shortest explanation is that these are fragments of Dante’s Inferno. Joyce was greatly inspired by the poetry of Dante, quoted by biographer Richard Ellmann as saying:

“I love Dante as much as the Bible. He is my spiritual food….”

Joyce loved Dante so much in fact that early in his life he asserted that The Divine Comedy was Europe’s only true epic, though later in life he backtracked. Another Joyce quote via Ellmann:

“Dante tires one quickly; it is like looking at the sun. The most beautiful, most human traits are contained in the Odyssey.”

Nonetheless, Dante’s influence can be felt throughout Ulysses. Both Ulysses and The Divine Comedy deal with an Odyssey-like journey, themes of exile, and unflattering literary portraits of folks from the author’s hometown. Scholars love to debate whether Bloom or Dedalus is more analogous to the fictionalized Dante in The Divine Comedy, but that’s a conversation for another day. Here in “Aeolus,” in an episode dedicated to journalism and prose, when young Dedalus needs a poetic escape hatch, he reaches for Dante.

The scene from the Inferno quoted by Stephen is from Canto V, during which Dante meets the adulterers Francesca and Paolo. The lovers were murdered by Francesca’s husband when their affair was discovered, and they were condemned to spend eternity buffeted by winds as punishment for their wanton ways. The wind motif fits snugly into “Aeolus,” which is jam packed with windy imagery. This is a nice, hidden expression of this motif. If you know, you know (and now you know). Stephen is also tormented by infernal visions and corpse-chewing ghouls both in Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, so the visions of hell found in the Inferno fit his mindset quite well.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1862

Getting back to the intrusion in “Aeolus”, the Italian reads in English (from Gifford and Seidman’s annotation):

“........................ thy peace

.................. it pleases thee to speak

while the wind, as now, is silent for us.”

It’s a truncated version of Dante’s original, but the “while silent is the wind” bit is key. In the Inferno, the winds are quieted long enough for Dante to speak to Francesca and Paolo. In “Aeolus”, the “winds” of the newsmen are quieted for Stephen as long as he is able to retreat into his mind.

The complete original reads:

“If the King of the Universe were our friend, we would pray him for thy peace: seeing thou hast pity of our perverse misfortune. Of that which it pleases thee to speak and hear, we will speak and hear with you, while the wind, as now, is silent for us.”

Scholar Sara Sullam points out that the omissions are particularly striking in the Dante intrusion. Stephen focuses consciously on the rhyme, yes, but the way in which he has truncated the verse calls attention to the rhythm rather than the rhyme. In Sullam’s view, Stephen is searching for a rhythm in addition to a rhyme for his vampire poem. There are a few clues in the words Stephen has chosen to preserve. Let’s start with “la tua pace,” Italian for “your peace.” “Pace” is also an English word, and Joyce never met a pun or double entendre he didn’t love (see also: Finnegans Wake). Pace could refer to the rhythm rather than the rhyme of Stephen’s poem. Sullam quotes Joyce writing in his “Paris Notebook” about the importance of poetic rhythm:

“Rhythm seems to be the first or formal relation of part to part in any whole or of a whole to its part or parts… Parts constitute a whole as far as they have a common end.”

The rhythm of “Aeolus” derives from its correspondent organ, the lungs. Sullam notes a binary rhythm throughout the episode, casting a sense of inhalation and exhalation over the action of the busy newsroom. “Aeolus,” like the two men dressed the same, is timed in twos, in and out, inflating and deflating. A great example appears early in the episode in the description of Ruttledge’s door:

“The door of Ruttledge's office whispered: ee: cree. They always build one door opposite another for the wind to. Way in. Way out.”

Notice the direct mention of wind alongside the musical “ee: cree” and the rhythmically satisfying “Way in. Way out.” Richard Ellmann points out other doubled up phrases like, “Thumping. Thumping.” and “Clank it. Clank it.” that contribute to the rhythmic flow of the episode. Ellmann even sees a mention of “scissors and paste” as getting into the swing of things:

“Red Murray's long shears sliced out the advertisement from the newspaper in four clean strokes. Scissors and paste.”

You can almost clap your hands to the rhythm of Red Murray’s four clean strokes – sci. ssors. and. paste. Stephen yearns to break free of this simplistic rhythm, though. In the next section, the rhyme and rhythm intensify:

“He saw them three by three, approaching girls, in green, in rose, in russet, entwining, per l’aer perso, in mauve, in purple,”

Sullam demonstrates how Stephen is now describing Dante’s rhyme scheme in the form of these approaching girls, just as he described his own rhyme scheme as the two men. Buckle up for another translinguistic pun.

Gustave Doré, 1860’s

Stephen precedes the RHYMES AND REASONS sequence with the question, “Would anyone wish her mouth for a kiss?” The Italian word for “kiss” is “bacio,” and there is a common Italian rhyme scheme called “rima baciata,” similar to an AABB rhyme scheme in English. Not quite the same as Hyde’s in “My Grief on the Sea,” but just as basic. Since rima baciata consists of rhyming pairs, Sullam believes that the “two men dressed the same, looking the same, two by two” are a metaphor for rima baciata, which travels two-by-two, but comes across a bit static and same-y, maybe even a little stale. These approaching, brightly-garbed girls travel in a trio, however. Their colors, a representation of Dante’s love of synaesthesia, and the fact that they are in motion suggests a more dynamic rhyme scheme, this time in a rhythm of three. Sullam says this represents Dante’s preference for the rhyme scheme of “terza rima,” meaning third rhyme, as it allows more flexibility and narrative possibilities. Basically, Dante’s dynamic rhymes are a better inspiration for Stephen’s poetic development than staid poetry like Hyde’s.

The language in the description of the girls is similar to some of the descriptions found in Canto XXIX of Purgatorio. This canto describes an allegorical heavenly pageant that precedes the arrival of Beatrice and the final book of The Divine Comedy, Paradiso. As we look into Purgatorio’s Canto XXIX, we see some old friends. Dante describes:

“I saw two aged men, unlike in raiment, but like in bearing, and venerable and grave."

Of course, these are the pair of men Stephen alludes to earlier. For Dante, these grim aged men represent the Acts of Apostle and the epistles of Paul. Dante also describes a group of maidens arrayed in bright colors, representing the theological virtues and the four cardinal virtues. To read a more detailed breakdown of Canto XXIX’s procession (and the rest of The Divine Comedy), I recommend Columbia University’s Digital Dante. Joyce’s descriptions in this brief passage also serve as a bridge between Francesca in Hell and the Virgin Mary in Heaven. Now, more Italian:

“...quella pacifica oriafiamma, gold of oriflamme, di rimirar fè più ardenti.”

This is taken from Canto XXXI of Paradiso, in which Dante describes a vision of heaven. Guided through Heaven by St. Bernard, Dante witnesses “that peaceful oriflamme” shining over heaven, and in the center “more than a thousand angels making festival” with the Virgin Mary in their midst.

The Virgin’s overwhelming beauty is likened here to the oriflamme, the medieval standard of the kings of France. When the oriflamme was flown in battle, it meant that the French army would take no prisoners and show no mercy. Legend held that it was given to the kings of France by the angel Gabriel and thus showed God’s favor for the French. Therefore, an army fighting under this banner could never be defeated. The oriflamme was captured by the English at the battle of Crécy and flown for the final time at Agincourt, two famous French defeats, so it seems God may have had other plans.

The Oriflamme

For our context here, I think Dante is calling attention to the sunburst in the center of the oriflamme, symbolic of the radiance of the Blessed Virgin. In the second bit of Italian, “di rimirar fè più ardenti,” Dante says that St. Bernard “made mine eyes more ardent to regaze,” meaning that St. Bernard looked upon the virgin so passionately that Dante couldn’t resist looking upon her again.

What is Stephen going for here? His recitation of Dante has proceeded from Francesca and Paolo’s damnation, through Purgatory to the ineffable beauty of the Mother of God in Heaven. Some commentators, such as William York Tindall, quoted by scholar Carole Slade, see this as representative of Stephen’s own progress from the hell of his own personal history to a more heavenly state. Others, such as Robert Adams Day, see this as a continuation of the allegory about poetic rhyme and rhythm. Stephen’s staid rhyme scheme is like those men walking two-by-two, as we’ve discussed, but these colorful cavorting maidens and the blinding beauty of heaven are symbolic of Dante’s transcendent verse. Stephen’s progress is not from a literal hell to heaven, but symbolic of how far he has yet to go as a writer. It’ll be a long while yet before his work is preserved in the Library of Alexandria:

“But I old men, penitent, leadenfooted, underdarkneath the night: mouth south: tomb womb.”

We’re back in Purgatorio, Canto XXIX at the heavenly procession. The line alluded to here reads:

“Then saw I four of lowly semblance; and behind all, an old man solitary, coming in a trance, with visage keen.”

In Dantean allegory, the four men are representative of the minor epistles of the New Testament, and the lone, old man is the Book of Revelation. The apocalyptic visions of Revelation could certainly be taken as “leadenfooted, underdarkneath the night,” but let’s consider them as allegory. Stephen’s clunky verse appears so grim and plodding compared to Dante’s light, colorful waltz of words. We see again the influence of Dante’s synaesthesia here as the dark color of night is used to confer a dour personality onto Stephen’s poetry in contrast to the mauve, russet, rose and green of Dante’s.

Sullam points out that to understand the depth of this allegory, we must also consider Stephen’s surroundings. He’s in the house of industrial printing, where literal leaden letters are pressed together systematically by machines. This mechanized production of writing stands in contrast to the light, playful dance of handwritten manuscript. This is particularly meaningful to Stephen who sees the pen as his main defense against the world outside his head. Recall how even modern-minded Bloom describes the printing press early on in “Aeolus,” as blunt, inhuman, unthinkingly violent:

“Machines. Smash a man to atoms if they got him caught. Rule the world today. His machineries are pegging away too. Like these, got out of hand: fermenting. Working away, tearing away.”

Sullam adds an additional layer of meaning to this passage, particularly in the usage of “leadenfooted.” The “leaden” aspect is the typographical characters as mentioned above, heavy and standardized. “Footed” could refer to poetic foot, a term for the rhythm and pace of poetry. Stephen is vexed by his heavy handed, ungraceful rhymes - south and mouth, womb and tomb (a callback to “Proteus”) - and sees no life in them.

“Tomb womb” is a notable juxtaposition of death and life. I find it interesting that they are ordered “tomb” before “womb,” as the space between those two experiences is not life, but the bardo, where you may be beset by hungry ghosts between your death and next rebirth. (That part didn’t make it into The Divine Comedy).

Hungry Ghosts scroll, 12th c. Japan

“—Speak up for yourself, Mr O’Madden Burke said.”

I find this closing line, an interjection from the world outside Stephen’s mind, particularly interesting. One reason Dante depicts Francesca in Hell, apart from her adultery, is because she refuses to admit her sin. She blames Paolo and even the concept of love itself for her infidelity, anyone but herself. Her inability to admit guilt and her rejection of agency over her sin make her unable to repent, and thus she is eternally buffeted by the winds of Hell. Stephen, if you recall, is bogged down in guilt because he refused to pray for his dying mother, as she requested. He feared being dragged back into the world of Catholicism, unable to escape back into his hyperborean existence afterward.

Stephen is unwilling or unable to admit that what he did was, at the very least, unkind to his mother. He cannot alleviate his guilt until he admits that he is guilty of this sin. When confronted by his mother’s angry spirit in “Circe,” he finally speaks up for himself, with a confident, “Non serviam,” meaning “I will not serve,” the words of Lucifer to God in Paradise Lost. Stephen chooses to reject the morality of a medieval mind like Dante’s. It seems Joyce made a similar artistic choice in his life. Ellmann wrote that, though Dante seems to have been Joyce’s favorite author, Joyce himself favored a less retributive view of human relationships, setting aside the medieval view of heaven, hell, sin and punishment, and instead the “relish[ing] secular, disorderly” relationships that Dante would have ignored or punished.

Further Reading:

Bowen, Z. (1974). Musical allusions in the works of James Joyce: Early poetry through Ulysses. Albany: State University of New York Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y9erlwtw

Day, R. (1980). How Stephen wrote his vampire poem. James Joyce Quarterly, 17(2), 183-197. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476277

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Jokinen, Anniina. "The Oriflamme." Luminarium Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/oriflamme.htm

Mikics, D. (1990). History and the Rhetoric of the Artist in “Aeolus.” James Joyce Quarterly, 27(3), 533–558. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25485060

REYNOLDS, M. T. (1993). DANTE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF JOYCE’S MODERNISM. Lectura Dantis, 12, 75–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44806515

Slade, C. (1976). The Dantean Journey through Dublin. Modern Language Studies, 6(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/3194386

Sullam, S. (2003). Inspiring Dante: The Reasons of Rhyme in Ulysses. Papers on Joyce, 9, 59067. Retrieved from http://www.siff.us.es/iberjoyce/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/6-Inspiring-Dante-Proofed-and-Set1.pdf

Thornton, W. (1968). Allusions in Ulysses: An annotated list. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/ucwq3x7