Decoding Dedalus: The Opal Hush Poets

“The first spectre of the new generation has appeared. His name is Joyce. I have suffered from him and I would like you to suffer.” - Æ to W.B. Yeats, 1902

This is a post in a series called Decoding Dedalus where I take a passage of Ulysses and break it down line by line.

The passage below comes from “Aeolus,” the seventh episode of Ulysses. It appears on page 140 in my copy (1990 Vintage International). We’ll be looking at the first paragraph in the passage headlined “A MAN OF HIGH MORALE.”

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

In Ulysses’ seventh episode, “Aeolus,” Stephen Dedalus finds himself upended amidst a whirlwind of rhetorical flourish, as the older men in the newsroom of the Evening Telegraph defend their favorite bits of journalism and oratory. As J.J. O’Molloy finishes describing the unsurpassed courtroom speechifying of Seymour Bushe, he turns to Stephen to confirm a rumor:

“—Professor Magennis was speaking to me about you, J. J. O’Molloy said to Stephen.”

Professor William Magennis was a real professor at University College Dublin while James Joyce was a student there in the early 1900’s. In Ulysses Annotated, Don Gifford and Robert Seidman refer to Magennis as “something of an arbitrator on the Irish literary scene,” as well as a supporter of young Joyce. For an aspiring but undiscovered poet like Stephen, recognition from someone like Magennis could make the difference between literary accolades and total obscurity.

While Magennis may have been a man of the very highest morale, he had no taste when it came to the future of literature. Magennis was an advocate for censorship of the arts and spent much of his later life on a crusade against “evil literature,” even describing Ulysses as “moral filth.” Writer Frank O’Connor in turn described Magennis as “a windbag with a nasty streak of malice.”

“What do you think really of that hermetic crowd, the opal hush poets: A. E. the mastermystic?”

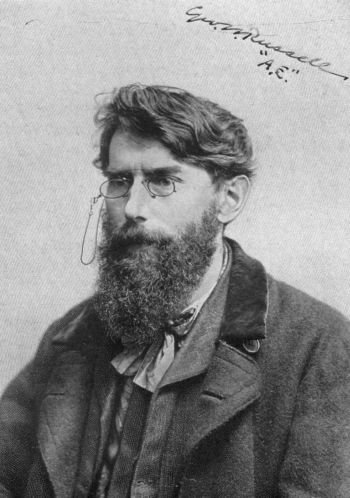

Æ

The conversation takes an abrupt and unhappy turn for poor Stephen, though. It seems Magennis wasn’t gushing to O’Molloy about Stephen’s unparalleled literary genius but rather expressing concern about the odd company the young artist has been keeping these days.

A.E. (or rather, Æ) is George Æ Russell, who Stephen does, in fact, meet up with later in Ulysses’ ninth episode, “Scylla and Charybdis.” Russell, indeed a mastermystic, styled himself as “Æ,” short for “æon,” which according to Slote, Mamigonian and Turner’s Annotations to James Joyce's Ulysses, carries the theosophical meaning of “an emanation from Deity, and the medium of its expression.”

Æ founded the Dublin Hermetic Society in the late 1890’s after defecting from the Dublin Theosophical Society. Hermeticism is a system of ceremonial magic developed based on the teachings of the mysterious Hermes Trismegistos. It was the basis for occult groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, whose members included folks like W.B. Yeats and Maud Gonne, though its origins are believed to be far older. Occultism was very much in vogue amongst Dublin intellectual circles at this time, so it’s no surprise that Stephen (or Joyce) would have at least a passing interest in the subject.

While O’Molloy frets a bit over Stephen associating with such a peculiar figure, describing Æ as merely a mystic weirdo is selling his cultural influence short. Æ was also a painter, poet, and dedicated Irish Nationalist. He was particularly focused on agrarian reform, writing for and later serving as editor for the Irish Homestead. In fact, it was Æ who first published Joyce’s short story “The Sisters” in the Irish Homestead in 1904 under the pseudonym Stephen Dedalus. Æ asked Joyce for something simple and rural that wouldn’t shock his readers, something to play to “the common understanding.” Not exactly Joyce’s forte, but Æ would go on to publish several more of Joyce’s short stories before the complaint letters piled too high.

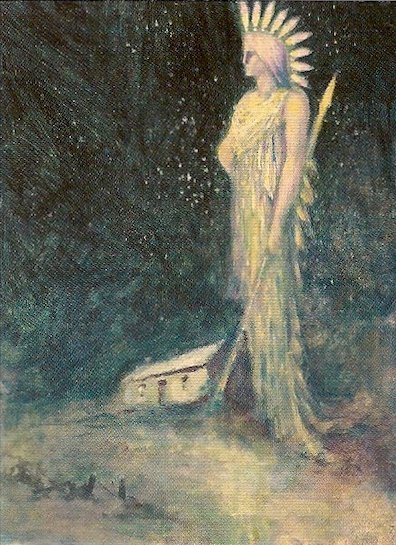

“The Stolen Child,” Æ

O’Molloy lumps Æ and the hermetics in with the “opal hush” poets when he questions Stephen. We can infer from the context that this nickname is not complimentary, but what does it actually mean? Gifford and Seidman wrote in Ulysses Annotated that “opal hush” refers to two of Æ’s favorite and most frequently employed poetic words, but this is not quite accurate. The true story belongs to one of my favorite subgenres of Blooms & Barnacles story: a nearly-forgotten, low stakes literary spat.

Russell used the Irish Homestead to showcase the work of poets with a similar mystical aesthetic, but it wasn’t beloved by one and all. In the early 1900’s, the Homestead had caught the ire of a rival publication, The Leader. Founded by D.P. Moran in 1900, The Leader promoted the idea of “Ireland for the Irish,” taking a hardline stance on the promotion of Catholicism over Protestantism, and of Irish goods and industry. Moran took very seriously the battle of “Gael vs. Pale”, as he framed it, pitting the traditional Gaelic culture of rural Irish life against the urban, Protestant elite of the Dublin Pale, which included the likes of W.B. Yeats and Russell. Joyce would have been lumped into Team Pale as well despite his Catholic background as the Leader abhorred anyone too urban, educated or middle class, regardless of religious affiliation.

It seems like Moran and Æ could have been allies, as they were both concerned with Irish Nationalism and the promotion of an idealized rural lifestyle. Moran’s hardline support of Catholicism and cynicism toward the overly earnest Celtic Twilight writers of the Homestead left them at odds, however. Moran and his writing staff were devastatingly adept at coining disparaging nicknames for their many enemies. Æ, for instance, was dubbed “the Hairy Fairy” by the Leader, and indeed Æ was a beardy fellow with a penchant for painting images of the mythical sidhe, or fairies. The Leader’s nicknames had a way of catching on, though, and “Hairy Fairy” still pops up alongside Æ’s name in a Google search 12 decades later.

This rivalry came to a head in late 1903, when the Leader’s Imaal (pen name for a reviewer called J.J. O’Toole) took aim at the Irish Homestead’s Christmas Issue, particularly its poetry. Imaal sunk his teeth into a poem entitled “Grey” by Alberta Victoria Montgomery, which contained the fateful lines:

“The opal hush lies on the cloud bars bright,

A calm content sounds now in evening’s sigh.”

Imaal responded to Montgomery’s verse with:

“I don’t quite know what an ‘opal hush’ may be, but I feel sure the writer must have felt ‘Celtic’ through and through after writing the mystic words.”

Thus, a terrible catchphrase was born.

“Opal hush” became a term of derision for the mystically-minded Celtic Twilight writers and was regularly deployed by the Leader to ridicule them. The term reached its peak in 1904, just in time for it to be in the zeitgeist when O’Molloy questions Stephen’s acquaintanceships, but it continued to appear in print (at least in the Leader) into the 1920’s, such as this warning about the enemies of the True Gaelic Irish found in a 1923 edition:

“Luminous,” Æ

“...the Opal Hushers, the Hairy Fairies, the Celtic Notaries, the literary British Pensionars [sic] are attempting to reorganise for an offensive against Irish-Ireland…”

The targets of the Leader’s bile seem to have reclaimed the epithet “opal hush” to a certain extent, or at least just became an in-joke. They even created a signature cocktail called the opal hush that was enjoyed at parties in London’s aesthetic circles well into the 20th century. Legend has it Yeats invented the opal hush, but its true origin remains shrouded in myth. It was also said to be a favorite of Pamela Colman Smith, the artist of the iconic Rider-Smith-Waite tarot deck. And since you’re dying to know, you can make your own opal hush at home. Simply fill a wine glass one quarter full with red claret and then fill the other three quarters with lemonade from a soda siphon.

O’Molloy isn’t finished with Dublin’s esoteric community, though:

“That Blavatsky woman started it. She was a nice old bag of tricks.”

“Blavatsky” is Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, a late-19th century spiritual movement that borrowed concepts from Eastern religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as Western practices of the time, such as seances and channeling. Theosophy was fashionable among intellectuals around the turn of the 20th century, and the Dublin Theosophical Society’s founders included Yeats and Russell before they drifted away to hermeticism.

Madame Blavatsky

Of course, Blavatsky and Theosophy had their detractors. O’Molloy quickly refers to her as a “nice old bag of tricks.” Long before O’Molloy’s questions to Stephen, Blavatsky had been accused of faking the supernatural phenomena at her meetings. Richard Hodgson of the Society for Psychical Research wrote in his 1885 investigation of Blavatsky’s techniques that she “has achieved a title to permanent remembrance as one of the most accomplished, ingenious, and interesting impostors of history.”

By 1904, Theosophy was already on the wane in Dublin’s intellectual circles, but it seems to have at least briefly piqued the interest of a young James Joyce. According to his younger brother Stanislaus, James dabbled in occult philosophy in his early 20’s as a replacement for Catholicism before ultimately abandoning it altogether. Joyce’s personal library included works by prominent theosophists like Blavatsky, Henry Olcott, and A.P. Sinnett, though, and the theosophical references in Ulysses make it clear that he had more than a passing familiarity with the core beliefs of Theosophy.

For example, just a few headlined sections beyond this passage, under the banner “OMINOUS - FOR HIM!” Stephen imagines Daniel O’Connell’s famous rallies at Mullaghmast and Tara. He concludes with:

“Gone with the wind. Hosts at Mullaghmast and Tara of the kings. Miles of ears of porches. The tribune’s words, howled and scattered to the four winds. A people sheltered within his voice. Dead noise. Akasic records of all that ever anywhere wherever was.”

Stephen openly references the Akasic record, a concept directly taken from Theosophy. The Akasa (usually spelled Akasha) or Akasic record has many names (Yeats, for instance, called it the anima mundi), but it refers to the idea of an infinite and indestructible record of all history that exists outside of the physical plane. It’s notable here because Stephen refers to it directly by name, demonstrating that he has an understanding of the concept, possibly via his acquaintanceship with Æ. Stuart Gilbert writes in his book Ulysses: A Study that the indestructibility of words and thoughts was particularly fascinating to Joyce, enough so that he included it in Ulysses.

In his article “James Joyce and the Theory of Magic,” Craig Carver writes that through study and discipline, one can learn how to access the infinite knowledge of the Akasa but that some individuals can naturally access it via what Carver terms “emancipated spiritual faculties,” and it seems that Stephen has just such a faculty. We’ve explored this idea in the past on the blog with regards to Stephen’s Viking timeslip on Sandymount Strand.

One interpretation, then, of Stephen’s reference to O’Connell’s speech is that he is not simply remembering it as a historic event, but that hearing MacHugh’s recitation of Taylor’s speech is causing Stephen to slip again and experience O’Connell’s speech via the Akasic record, so powerful is the rhetoric. A few paragraphs on, Stephen once again invokes the Akasic record as he recalls the details of his “Parable of the Plums:”

“Damp night reeking of hungry dough. Against the wall. Face glistering tallow under her fustian shawl. Frantic hearts. Akasic records. Quicker, darlint!”

This is the same memory of a late night encounter in Fumbally’s Lane that Stephen tried to conjure back in “Proteus.” The Akasic record records everything equally, whether it’s the soaring rhetoric of Daniel O’Connell or the scattered memory of a sex worker in a dark, dirty alley. Even further back in “Telemachus,” Stephen describes the memory of his late mother as “folded away in the memory of nature with her toys.” In his book The Growth of the Soul, theosophist A.P. Sinnett refers to the Akasic record as the “infinite memory of Nature,” suggesting that this is the source for Joyce’s verbiage here. An indestructible, eternal memory is appealing to a young man caught in the throes of grief such as Stephen.

So, Joyce had a working knowledge of theosophical concepts, even owning books on the subject. Books were not his only source, though:

“A. E. has been telling some yankee interviewer that you came to him in the small hours of the morning to ask him about planes of consciousness.”

In the early 1900’s, University of Pennsylvania professor Cornelius Weygandt visited Dublin in order to interview well-known Irish writers for a book on the Irish literary scene. Weygandt interviewed Æ, who relayed the story of an “ardent young countryman” he found waiting for him near his home late one night in the summer of 1902. The young man, who Weygandt refers to only as “the boy” throughout the anecdote, revealed he had been waiting around two hours to have the chance to talk to Æ. The boy is initially reluctant to reveal why he’d sought out Æ, but eventually opens up and the two converse into the wee hours of the morning. The story is also recounted in Richard Ellmann’s biography of Joyce, and though the accounts diverge slightly, they both agree that this “boy” was a bit intense, curious, and quite critical of Æ.

“The boy” was of course our young Artist. Joyce made quite an impression on Æ, who announced the advent of Joyce to his artsy friends. He wrote to artist Sarah Purser soon after the meeting:

“I wouldn’t be [Joyce’s] Messiah for a thousand million pounds. He would be always criticising the bad taste of his deity.”

A few months later, Æ wrote to W.B. Yeats, encouraging him to meet with Joyce when he next visited Dublin:

“The first spectre of the new generation has appeared. His name is Joyce. I have suffered from him and I would like you to suffer.”

Æ’s first impression of 20-year-old Joyce, as it turns out, was perfectly on the nose:

“Magennis thinks you must have been pulling A. E.’s leg. He is a man of the very highest morale, Magennis.”

As Ellmann tells it, Joyce’s friends thought he must have gone to Æ’s home as a prank on the bearded mystic. While Joyce dismissed Theosophy as a “recourse for disaffected Protestants” in the end, he still went to Æ in earnest. The meeting with Æ was a means to an end. The intellectual scene in Dublin was enamored with occultism, so the way in for a young man with no connections was through the head occultist. Additionally, Æ lived in Dublin full-time and so was most accessible to young Joyce compared to someone like Yeats who was often away. Joyce could take or leave the planes of consciousness, but he wanted to use Æ as a way into Dublin’s elite literary scene. Joyce’s plan worked, in a way. Æ published his stories, Yeats and Lady Gregory supported his early career, and all three loaned him money until too many loans went unpaid. Joyce rewarded all three by trashing them in his poetry and prose alike.

Æ’s legacy within the text of Ulysses, extends beyond his cameo in “Scylla and Charybdis.” Joyce incorporated occult concepts such as metempsychosis and the Akasic record into Ulysses, as we’ve explored in this post and others, but Ulysses’ system of correspondence also likely originates in the occult. A central concept of hermetic thought is the reflection of the microcosm in the macrocosm, and vice versa, a belief encapsulated in the hermetic maxim, “as above, so below.” Ordinary people and objects can take on powerful, symbolic resonance with an understanding of a system of correspondences. Ulysses is built upon just such a system of correspondences, as anyone who’s ever picked up a reading guide is surely aware. This internal framework of correspondences allows Ulysses as a mere novel to encompass the depth and breadth of human experience through its system of correspondence, the microcosm of the novel as a reflection of the macrocosm of human experience. If Ulysses contains all of human experience, then it is its own sort of Akasic record, immutable and utterly complete. An occult tome, if ever there was one.

Further Reading:

Carver, C. (1978). James Joyce and the Theory of Magic. James Joyce Quarterly, 15(3), 201-214. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476132

Coleman, M. (2009). Magennis, William. In Dictionary of Irish biography. https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.005338.v1

Deane, V. From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay Area: the Afterlife of Opal Hush. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-allusions/opal-hush

Deane, V. (2012). Joyce, Moranism, and the Opal Hush Poets. Dublin James Joyce Journal 5, 66-81.

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Gilbert, S. (1955). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Kain, R. (1962). The Yankee Interviewer in Ulysses. In M. Magalaner (Ed.), A James Joyce miscellany. Southern Illinois University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yh7ndmw8

Morrisson, M. S. (2009). “Their Pineal Glands Aglow”: Theosophical Physiology in “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 46(3/4), 509–527. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20789626

Slote, S., Mamigonian, M., and Turner, J. (2022). Annotations to James Joyce's Ulysses. Oxford University Press.

Terrinoni, E. (2007). Occult Joyce: The hidden in Ulysses. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/zrzasu6a

Tindall, W.Y. (1954). James Joyce and the Hermetic Tradition. Journal of the History of Ideas, 15(1), p. 23-39. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y3jt7uwp

Weygandt, C. (1913). Irish plays and playwrights. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/2p9ea679