The Invincible Ignatius Gallaher

“And yet it was in some way if not as memory fabled it.” - Stephen Dedalus

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

It seems that poor Stephen Dedalus can’t catch a break from the nightmare of history anywhere in this bloody city.

While Stephen’s presence in “Aeolus” is more appreciated by the newsmen than Bloom’s, he is still subjected to Evening Telegraph editor Myles Crawford’s schooling on various historical topics. Ironically, Stephen is visiting the newsroom at the behest of another aging blowhard, his employer Mr. Deasy who is leaning on Stephen’s journalistic contacts to get his letter published. Whereas Deasy treats Stephen as a sullen errand-boy, Crawford knows that Stephen is capable of more than delivering think-pieces about foot and mouth disease:

“—I want you to write something for me, he said. Something with a bite in it. You can do it. I see it in your face.”

Bird-beaked and aureoled like moony-headed Thoth, Crawford, our resident bird of augury, holds the power of premonition. Just as he correctly predicted the First World War, here he foretells Stephen Dedalus’ future:

“Give them something with a bite in it. Put us all into it, damn its soul. Father, Son and Holy Ghost and Jakes M’Carthy.”

Or rather, he envisions Stephen’s future in a parallel timeline where he is named James Joyce. One day young Dedalus will write the story of his Dublin Days in the early 20th century, including the people he knew there as characters. In this timeline, it seems, folks are excited to be included in his work, whereas in Joyce’s timeline, reactions ranged from hurt feelings to litigiousness.

Crawford doesn’t linger long on Stephen’s gifts, however. In fact, Stephen will later offer up “something with bite in it” - his “Parable of the Plums” - and Crawford will reject Stephen’s creative expression out of hand. Crawford is mainly interested in journalistic scoops, fawning over the famed Dublin journalist, Ignatius Gallaher. Crawford, like many of those past their prime, dismisses the younger generation, favoring instead memories of past glory. He laments:

“Where do you find a pressman like that now, eh?”

Ignatius Gallaher, whose brash, bombastic personal style is familiar to anyone who has read the short story “A Little Cloud” in Dubliners, is a fictionalized version of Fred Gallaher, legendary Dublin journalist and Joyce family friend. In fact, Fred’s brothers Gerald and Joe are also mentioned in Ulysses, though much more briefly. Gallaher the journalist was quite a bit older than James Joyce, and by the time Joyce came of age, Gallaher had left Dublin for good, so it’s likely that the stories about Gallaher remembered by Joyce came secondhand from his father and his friends. Gallaher was, in fact, a sports reporter, covering mainly horse racing, and a regular fixture at The Ship where Stephen was supposed to have met Haines and Mulligan instead of going to the Evening Telegraph office.

Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Peter Paul Rubens, 1600’s

Gallaher’s father, John Blake Gallaher, was the chief sub-editor at the Freeman’s Journal when Fred got his first job there at age 15. Like another well-known, bombastic Joyce friend, Fred Gallaher saved a woman from drowning. He never took water with his whiskey and apparently looked a bit like Ignatius Loyola, hence his Joycean pseudonym. More than anything, his personality distinguished him. John Mallon, the detective who investigated the Phoenix Park Murders, recalled:

“When there was adventure about, that involved scheming and feverish excitement and danger, it was impossible to keep Fred Gallaher quiet. And nothing appealed to him like the most extravagant and reckless propositions.”

Which brings us to Gallaher’s notoriety, bundled up in the nightmare of history, as recounted by one Myles Crawford. In “Aeolus,” the editor breathlessly regales Stephen with the tale of how Gallaher contrived a secret code based on a Bransome’s Coffee advertisement to transmit secret information about the Phoenix Park Murders to the New York World, securing his scoop in the international press and his legacy in Irish journalistic history:

“Gallaher, that was a pressman for you. That was a pen. You know how he made his mark? I’ll tell you. That was the smartest piece of journalism ever known. That was in eightyone, sixth of May, time of the invincibles, murder in the Phoenix park, before you were born, I suppose. I’ll show you.”

Crawford, as ever, is fascinated with Irish Nationalist political history. Initially, he seems to be giving Stephen a little insight into a great moment of journalistic excellence, but as the story progresses, it’s clear he’s telling it mainly for his own enjoyment. The other men don’t seem as enraptured listening as he is telling, adding few remarks other than Lenehan’s too-cute, “Clamn dever.” This may be because this is the eleventieth time they’ve all heard the story, or it may be because Crawford botches the details just as badly as he did with the 1798 exploits of the North Cork Militia in Ohio.

Well, maybe not as badly as that.

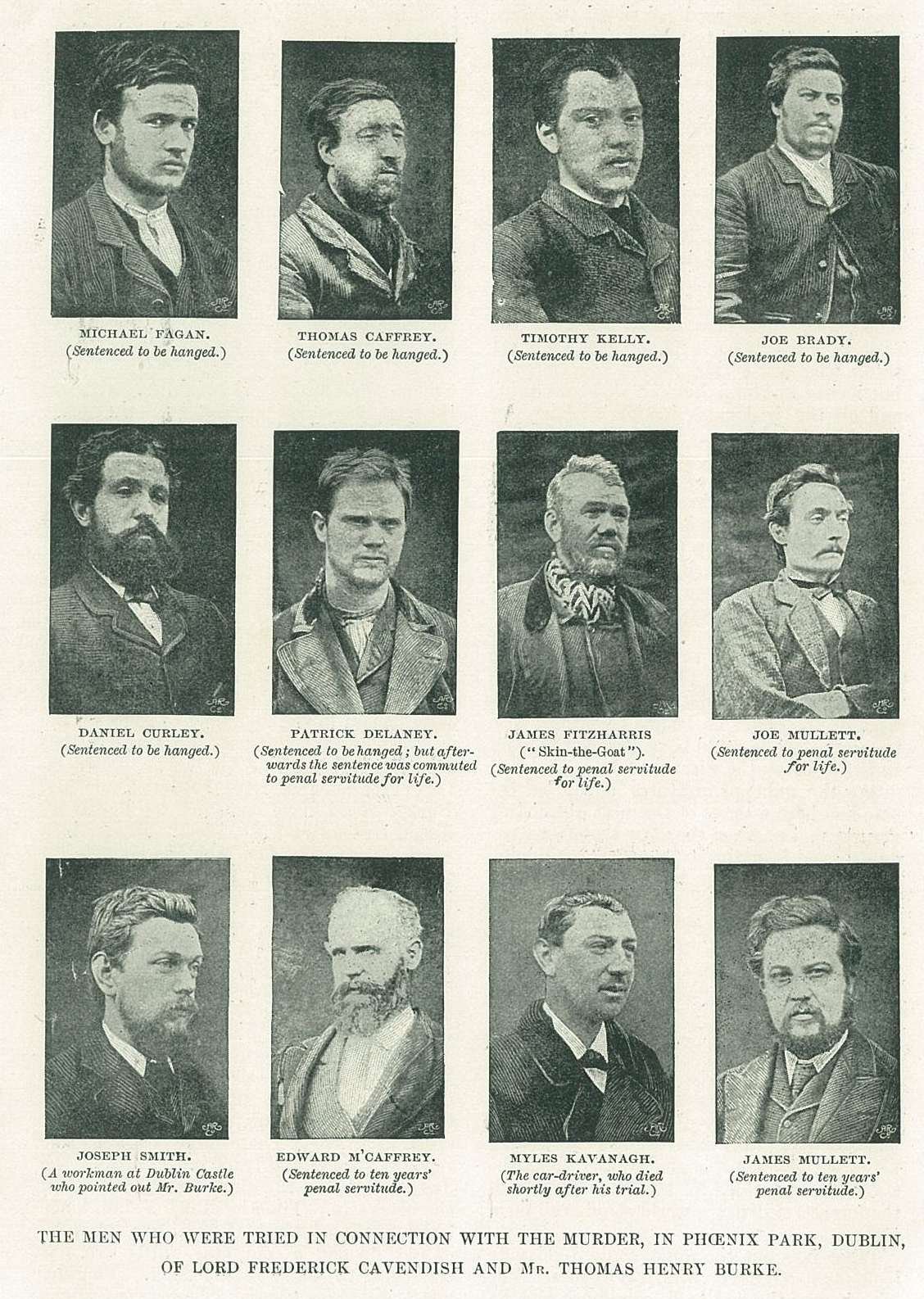

For a little background, the Phoenix Park Murders were a major political assassination in the spring of 1882. While walking through Dublin’s Phoenix Park on the evening of May 6, Permanent Under Secretary Thomas Burke and newly appointed Chief Secretary of Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish were waylaid by a group of knife-wielding assassins. Both Burke and Cavendish were killed, leaving the United Kingdom, and the world, stunned by these brazen political murders carried out in broad daylight in a major city. The Invincibles, a splinter group of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (Fenians for short) claimed responsibility.

Part of the shock arose from the target - Cavendish had only arrived in Ireland that day as a replacement for the deeply unpopular William Forster, who had also been the repeat target of would-be assassins. Secondly, while the Fenians were a well-known presence in Ireland, no one had ever heard of the Invincibles. The following year, James Carey, one of the Invincibles, squealed to the police and the jig was up for the Invincibles. In the end, five of Carey’s compatriots were hanged and Carey emigrated to South Africa, hoping to put the whole messy business behind him. In a surprise twist, one of the surviving Invincibles followed Carey to Cape Town, and shot the famous betrayer dead. So ends the tale of the Invincibles and the Phoenix Park Murders.

The shock and sensationalism of this grisly affair remained alive in the political imaginations of Dubliners like Myles Crawford into the following decades. The other men in the newsroom name two of the conspirators still living in Dublin - Gumley, who is “minding stones for the corporation” as a night watchman, and the colorfully named James “Skin-the-Goat” Fitzharris, who “has that cabman’s shelter, they say, down there at Butt bridge.” We’ll meet both of them in “Eumaeus”, Ulysses’ sixteenth episode.

The crux of Crawford’s story about Gallaher is his clever use of a Bransome’s coffee ad to transmit the route of the Invincibles’ getaway cab from the Phoenix Park:

“—F to P is the route Skin-the-Goat drove the car for an alibi, Inchicore, Roundtown, Windy Arbour, Palmerston Park, Ranelagh. F.A.B.P. Got that? X is Davy’s publichouse in upper Leeson street.”

Gallaher chose an ad for Bransome’s coffee in the March 17 edition of The Weekly Freeman, of which The New York World also had a copy on hand, and then used it as an ersatz map of Dublin to communicate the getaway route of the Invincibles in code. The journalistic sport attached to Gallaher’s clever scheming to overcome an information embargo just adds to the drama. It’s also where Crawford’s story completely falls apart.

Myles Crawford and the nightmare of history

Let’s begin with the date of the Phoenix Park Murders. Crawford says, “That was in eightyone….” but the murders took place May 6, 1882. This is such a glaring error, the first of several, and I think one of the reasons the other men in the newsroom choose to ignore Crawford. It’s an embarrassing error, as it is a date that any journalist worth their salt should know. Crawford is not totally alone in his error, as the narrator of “Eumaeus”, Ulysses’ 16th episode, remarks that the Invincibles “took the civilised world by storm, figuratively speaking, early in the eighties, eightyone to be correct.” In this case, the confident wrongness of “to be correct” adds a dash of irony to the comment. The depth and complexity of Crawford’s wrongness is truly astounding. Crawford says, presumably to Stephen, that the murders took place “before you were born.” If we take as given that Stephen shares a birthday with James Joyce (February 2, 1882), this is an accurate statement if Crawford is wrong (the murders happened on May 6, 1881), but wrong for the correct date (the murders happened on May 6, 1882). It’s a mess.

Another date to pay attention to is March 17, the publication date of the edition of The Weekly Freemen used by Gallaher for his map. The Weekly Freeman came out each week on Sunday, and in the years 1882, 1883 and even 1904, St. Patrick’s Day didn’t fall on a Sunday, so this couldn’t possibly have been the correct edition used by Gallaher. Furthermore, The Invincibles’ identities were totally unknown until Carey turned on his compatriots. Their identities would have been far more newsworthy than the route prior to their trial. Not to mention, the murders happened in May 1882 and their trial was in February 1883, so a March 17th scoop would have either been premonition or stale news. Ol’ Crawford couldn’t remember the year the murders took place in, though, so perhaps we can’t be too strict about this particular date.

Branson’s coffee

And what of the coffee ad? No such ad appeared in any of the issues of The Weekly Freeman during the relevant time period, in part because Bransome’s Coffee doesn’t exist. Branson’s Coffee, however, was a ubiquitous brand in Dublin during that era, so we can infer that our dear editor has even flubbed the name of the coffee. This would be like insisting on the validity of a Starbooks ad in our present day. It seems that without Mr. Bloom’s advertising expertise, Crawford is adrift. In his book Helen of Joyce, author Senan Moloney points out that “F.A.B.P.” is a shifted alphabet code that spells out “IDES” (see our blog post here about Bloom’s use of a similar code to conceal Martha’s address). Perhaps all this rigmarole about coffee is nothing more than a cleverly veiled comparison of the Phoenix Park Murders to the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Scholar Daniel P. Gunn also interprets the use of the coffee ad as figurative rather than literal in the context of Ulysses as a whole. Yes, it appears in the midst of a reasonably grounded anecdote, but it holds great symbolic power as well. We see Gallaher constructing a symbolic lattice atop a piece of popular ephemera, a habit perfected by one Mr. James Joyce. Ulysses is constructed on an elaborate system of correspondences that confer hidden layers of meaning to seemingly mundane objects and people throughout the novel. Gallaher does the same in Crawford’s anecdote, though with different ends in mind. Gunn points out that the Invincibles took a circuitous route home, just as Odysseus did. Some of the names on Crawford’s map evoke places in The Odyssey; perhaps Windy Arbour is the abode of Aeolus? Thus, The Odyssey is condensed into a map within Ulysses, within which a smaller version of The Odyssey is also hidden.

And what of Fred Gallaher? Was this story, with all its flaws, based on his life at all?

Sort of.

James “Skin-the-Goat” Fitzharris

Gallaher, though he was mainly a racing reporter, took a deep interest in the Phoenix Park Murders. The New York World did indeed have the murders on their front page for several days in 1882, though it’s not clear if that was due to Gallaher’s journalistic maneuvering. They didn’t print a secret getaway route in any case, as it was not known publicly until the following year. Gallaher was instrumental in helping American journalist Leander Richardson track down the real Skin-the-Goat for an exclusive interview before the police could find him once the Invincibles’ identities were known. Skin-the-Goat, a Dublin cab driver, drove a decoy vehicle to distract from the real getaway vehicle following the murders in 1882. He received a life sentence as an accomplice, but was released in 1903. It’s not clear if he really ran the cabman’s shelter by the Butt Bridge, though it seems more likely he had Gumley’s job of night watchman over a pile of rocks belonging to the Dublin Corporation.

Crawford also speaks of Joe Brady, who stabbed Burke, and Tim Kelly, who stabbed Cavendish:

“—New York World, the editor said, excitedly pushing back his straw hat. Where it took place. Tim Kelly, or Kavanagh I mean. Joe Brady and the rest of them. Where Skin-the-Goat drove the car. Whole route, see?”

Tim was a Kelly, never a Kavanagh as Crawford says. Crawford might be thinking of Michael Kavanagh, who drove the Invincibles’ real getaway vehicle (as opposed to Skin-the-Goat’s decoy). As an aside, Michael Kavanagh was confused with a Myles Kavanagh, adding another layer to the name confusion. Kelly and Gallaher were on fairly chummy terms during the Invincibles’ trial, as it turns out. The story goes that Kelly spotted Gallaher in court, and much to the shock of those in attendance, scribbled something on a paper and passed it to Gallaher. It turned out to be a bet on a horse. The horse ultimately lost his race. Fairing no better, Kelly was found guilty and hanged for murder.

James Carey, 1883

Gallaher was also able to secure a jailhouse interview with James Carey (whose name Bloom forgets in “Lotus Eaters”) after he informed on his fellow Invincibles. Carey was kept under tight lock and key, but his wife was granted visitation. Gallaher made the acquaintance of Mrs. Carey, and through her, snuck a list of questions to Mr. Carey. He wrote answers whenever he could and secreted the responses back to Gallaher via Mrs. Carey. No Branson’s coffee necessary.

The nightmare of history has fully ensnared poor, hapless Crawford. Our gallant editor functions as a nationalist foil for unionist Mr. Deasy, but it seems they have much in common despite their politics. Crawford rails against the ineptitude of the younger generation while utterly failing to tell a story that makes any sense about the older generation's golden boy. Furthermore, he’s encouraging Stephen to develop himself as a writer, clearly hoping to one day add him to the Evening Telegraph’s stable of reporters, while simultaneously ranting about how shit the youth are. Stephen has already been through this song and dance with Deasy. Now doubly alienated by the older generation, he chooses instead to zone out and think about his own creative pursuits in the form of his vampire poem:

“Mouth, south. Is the mouth south someway? Or the south a mouth? Must be some. South, pout, out, shout, drouth. Rhymes: two men dressed the same, looking the same, two by two.”

Stephen is attempting to self-soothe against the nightmare of history from which he cannot awake. For Stephen, this is the nightmare of his personal history. Early on in their conversation, as Crawford is telling him he can do something great, three phrases flash through Stephen’s conscious mind:

“See it in your face. See it in your eye. Lazy idle little schemer.”

These are the words uttered by the prefect of studies at Clongowes Wood College just before he beat Stephen with a pandybat for the crime of broken glasses. Stephen is clearly carrying this trauma. Though Crawford is encouraging Stephen’s talents, there is something in his grandstanding that triggers memories of the prefect. Perhaps it is a bit of imposter syndrome on Stephen’s end. In either case, Crawford’s manner turns Stephen off, thus he takes solace in his poetry and Dante.

Back in “Nestor”, Stephen said to Mr. Deasy, “I fear those big words which make us so unhappy.” Crawford’s story is an excellent illustration of why those big words can be so fearful. The Invincibles murdered two men in broad daylight in service of those big words, whether it be “justice” or “independence” or “nation” or all three. Joyce himself was no political radical, preferring Charles Stewart Parnell’s dream of a devolved government to the radical nationalism of groups like the Fenians and the Invincibles. Joyce wrote in 1912 of the Phoenix Park Murders:

“The Phoenix Park Murders represented a cruel, frontal assault on Parnellism, designed to derail an emerging alliance with Gladstone’s Liberal Party.”

James Carey, as the archetypal traitor, acts as a symbol of this political betrayal writ large. In Joyce’s eyes, writing before the even more dramatic political upheaval that would begin in 1916, this type of violent political carnage was antithetical to real, meaningful systemic change. Joyce was wrong at least in this regard, as the Phoenix Park Murders actually ended up strengthening Parnell’s position.

In “Eumaeus”, retired decoy getaway driver Skin-the-Goat foresees a “day of reckoning” on the way for England. Tiocfaidh ár lá. Bloom refutes him in his mind, finding this view to be “egregious balderdash,” though he admits to himself “a certain kind of admiration for a man who had actually brandished a knife, cold steel, with the courage of his political convictions….” Openly, Bloom says to Stephen, “I resent violence and intolerance in any shape or form. It never reaches anything or stops anything. A revolution must come on the due instalments plan.” Bloom is politically moderate, and I think this is close to Joyce’s own viewpoint.

The nightmare of history, then, manifests itself in the oversimplification and glorification of these tangled political events. History is reduced to nothing more than an anecdote about journalistic skill and a few, trite buzzwords. Scholar David Mikics writes:

“More significantly, the reduction of history to self-perpetuating, self-advertising clichés like ‘justice’ is itself revealed as an important mechanism of cultural authority.”

Perhaps this is what is contained in the coffee ad. The arc of history, our most tightly held ideals, our place in the body politic, life and death can all be reduced to a diagram on a coffee ad. Just as such an ad can make us crave a hot cup of joe, the right sequence of slogans can manipulate our feelings, outraging us about things that distract us from more meaningful pursuits, even from Truth itself.

Further Reading & Listening:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beck, H. The coffee riddle. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-environs/bransome-s

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Dwyer, F. (2016, Nov 23). The 1882 Phoenix Park Murders Part 1 - A fatal day in Dublin. The Irish History Podcast. Retrieved from https://irishhistorypodcast.ie/podcast-the-phoenix-park-murders-part-i-a-fatal-day-in-dublin/

Dwyer, F. (2016, Dec 1). The Phoenix Park Murders Part II - The Manhunt. The Irish History Podcast. Retrieved from https://irishhistorypodcast.ie/podcast-the-phoenix-park-murders-ii-the-manhunt/

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press.

Feeney, W. J. (1964). Ulysses and the Phoenix Park Murder. James Joyce Quarterly, 1(4), 56–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486461

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Gunn, D. P. (1996). Beware of Imitations: Advertisement as Reflexive Commentary in Ulysses. Twentieth Century Literature, 42(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.2307/441878

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Ito, E. (2000). The Phoenix Park Murders & Stephen's Parable of the Plums: An Analysis of "Aeolus". Journal of Policy Studies, 2(3), 257-270. Retrieved from http://p-www.iwate-pu.ac.jp/~acro-ito/Joycean_Essays/U07_phoenixparkmurders.html

Mikics, D. (1990). History and the Rhetoric of the Artist in “Aeolus.” James Joyce Quarterly, 27(3), 533–558. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25485060

Molony, S. (2006). The Phoenix Park murders: Conspiracy, betrayal and retribution. Mercier Press.

Molony, S. (2022). Helen of Joyce: Trojan horses in Ulysses. Printwell Books.

Mulhall, D. (2022, Jan 12). Invincible Joyce: The Phoenix Park murders in Ulysses. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/invincible-joyce-the-phoenix-park-murders-in-ulysses-1.4770046

Simpson, J. Ignatius per ignotius: The short life and extraordinary times of Frederick Gallaher 1: Making his way. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/gallaher/gallaher1

Simpson, J. Ignatius per ignotius: The short life and extraordinary times of Frederick Gallaher 2: Fred’s brilliant career with Sport and the Invincibles. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/gallaher/gallaher1