Weggebobbles and Fruit: Vegetarianism in Ulysses

“Joyce pretended to take an interest in fine dishes, but food meant nothing to him, unless it was something to do with his art…. He himself scarcely ate anything.” - Sylvia Beach

As Leopold Bloom approaches Nassau St. on his journey to lunch in “Lestrygonians”, Ulysses’ eighth episode, he is passed from behind by two figures, both of whom we’ve already “met” in the pages of Ulysses. Bloom identifies one as Geroge Æ Russell, mystic and literary tastemaker, and the other, Bloom speculates, could be the poet Lizzie Twigg. The two have a distinctly bohemian vibe that sets Bloom’s mind to wandering:

The corner of Nassau St. and Grafton St, c. 1910;

You can see Yeates & Son! (Image Source)

“His eyes followed the high figure in homespun, beard and bicycle, a listening woman at his side. Coming from the vegetarian. Only weggebobbles and fruit. Don’t eat a beefsteak. If you do the eyes of that cow will pursue you through all eternity. They say it’s healthier. Windandwatery though. Tried it. Keep you on the run all day. Bad as a bloater. Dreams all night. Why do they call that thing they gave me nutsteak? Nutarians. Fruitarians. To give you the idea you are eating rumpsteak. Absurd. Salty too. They cook in soda. Keep you sitting by the tap all night.”

Bloom suspects that the pair are coming from a nearby vegetarian restaurant. His mind is so geared towards food that he speculates about what they may have just eaten rather than trying to unravel their tantalizing conversation about tentacles and octopuses that he overhears in the previous paragraph. Since “Lestrygonians” is Ulysses’ food episode, let's speculate alongside Bloom on his peristaltic adventure through the city center. Once again:

“His eyes followed the high figure in homespun, beard and bicycle, a listening woman at his side…. Don’t eat a beefsteak. If you do the eyes of that cow will pursue you through all eternity.”

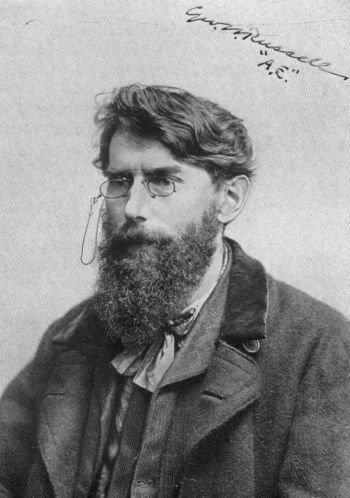

Æ, the “high figure in homespun, beard and bicycle,” did indeed follow a vegetarian diet, but only for about a year. There’s no evidence Lizzie was a vegetarian, or that she even knew Æ (see our profile of Lizzie Twigg). Æ was the founder of the Dublin Theosophical Society, and it was common for theosophists to follow a vegetarian diet due to their belief in reincarnation.

Coming from the vegetarian. Only weggebobbles and fruit.

There are two possible candidates for the vegetarian restaurant in which Bloom imagines the pair dined. One is Dublin’s very first vegetarian restaurant, the Sunshine Rooms, which was located in nearby Grafton St. The other, the College Vegetarian Restaurant, was located in College St., also just around the corner. Æ passes from behind as Bloom faces Grafton St., so it’s far more likely they would be coming from the College St. restaurant. The Sunshine Rooms didn’t survive long, while the College St. restaurant was in business into the 1920’s and played frequent host to Dublin’s alternative communities. More to the point, Æ was known to patronize the College St. restaurant. James and Margaret Cousins, friends of James Joyce as well as Æ, recall the restaurant specifically in their joint autobiography, We Two Together, as a “rendezvous for the literary set, of whom Æ was the leader. We frequently joined these idealists for lunch, and later met a number of Hindu vegetarians who had come to Dublin…”

Don’t eat a beefsteak. If you do the eyes of that cow will pursue you through all eternity.

Æ

So, what was the vegetarian scene in early 20th century Dublin like? Bloom correctly assesses that a vegetarian diet was often adopted for spiritual reasons in this era. There was a strong overlap in Dublin’s occult set and literary set, as exemplified here by Æ who was a hub in both worlds. Theosophy was heavily influenced by Eastern religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, both of which believe in reincarnation and practice vegetarianism. Bloom alludes to reincarnation in these comments, which was the chief reason for theosophists to avoid meat consumption.

Prior to the arrival of these Eastern influences in the 19th century, Western vegetarianism had an even earlier antecedent. The ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras, best known for that theorem you probably had to memorize in eighth grade math class, was a proponent of a vegetarian diet due to his belief in metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls. Therefore, at the risk of oversimplification, if you are eating an animal, you are eating a creature that potentially contains a formerly human soul. In fact, until the mid-19th century, vegetarians were often called Pythagoreans in Europe. Much of Pythagorean philosophy about diet and other topics survives largely due to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the work of literature in which Dedalus the artificer originates as well.

“They say it’s healthier. Windandwatery though. Tried it. Keep you on the run all day. Bad as a bloater. Dreams all night. Why do they call that thing they gave me nutsteak? Nutarians. Fruitarians. To give you the idea you are eating rumpsteak. Absurd. Salty too. They cook in soda. Keep you sitting by the tap all night.”

To Bloom, the existence of vegetarians implies the existence of fruitarians and nutarians. While “nutarians” may be a flight of Bloomian fancy, fruitarians do exist, though a fruitarian is an incredibly restrictive diet and can result in a number of serious vitamin deficiencies. If you do decide to take up the fruitarian lifestyle, though, you’ll be following in the footsteps of folks like Steve Jobs and Idi Amin, both of whom practiced fruitarianism for periods of their lives.

Bloom is open to some health fads (as evidenced by his interest in Eugen Sandow’s exercises). He clearly gave a vegetarian diet a go at some stage, though it didn’t agree with his constitution. If Bloomsday is a typical snapshot of Bloom’s diet, he mainly eats meat, bread, potatoes and cheese. Introducing a hefty amount of fiber to his system likely would result in a “windandwatery” effect, though it might just be Bloom experiencing regularity for the first time as his regular diet is quite unbalanced. We know from his narration in “Calypso” that he suffers from constipation, after all.

Bloom is haunted by memories of “nutsteak,” which seems to be some kind of early meat substitute. I was a vegetarian for around six years, and for me, the worst vegetarian dishes were things that pretended to be meat but weren't, so I sympathize with Bloom here. A burgeoning interest in an alternative diet isn’t always immediately accompanied by culinary skill. If you’re unlucky, you might end up eating alfalfa sprouts and mashed yeast in the Source Family restaurant like Woody Allen in Annie Hall. This may be why Æ only sustained his vegetarianism for a year.

Because of its association with intellectuals, mystics and artists, vegetarianism was seen as something that only wealthy people chose for aesthetic purposes, which is reflected in Bloom’s thoughts:

“Those literary etherial people they are all. Dreamy, cloudy, symbolistic. Esthetes they are.”

Bloom sees these alleged vegetarians as detached from normal life, as privileged, out-of-touch people following a weird fad diet. The first thing we learn about Bloom in Ulysses is that he loves to eat organ meat, so it’s no huge surprise that our Kidney King is dismissive of a plant-based diet.

Meat and potatoes were favored by the Irish in this era, but like vegetarianism, the choice to eat meat was also class-determined. Who got to enjoy a nice bit of roast with their evening meal depended on whether they could afford it. For most of Dublin’s working class, a meat-heavy meal would have been a rare occasion. This was even more true for farm laborers in rural Ireland. In this era, if you were wealthy, you might choose to have lunch in a vegetarian restaurant. If you were poor, you might get the potatoes, but have to forgo the meat.

Margaret and James Cousins (Image Source)

Of course, a big reason that Bloom is dismissive of vegetarians is that his creator was as well. James Joyce was supported early in his career by Æ, whose Irish Homestead first publish Joyce’s short stories. During a stint of homelessness in 1904, James and Margaret Cousins allowed Joyce to room with them briefly, though they asked him to move on due to non-payment of rent. Joyce, on the other hand, claimed that he couldn’t bear to stay there another moment due to “stomach trouble caused by a ‘typhoid turnip,’” a complaint against the Cousins’ vegetarian household. Despite the early support, Joyce grew increasingly alienated by the Dublin literary scene, in part due to its heavy political emphasis and in another part due to their refusal to continue publishing his work. In a letter to his brother Stanislaus, a young Joyce lashed out:

“And so help me devil I will write only the things that approve themselves to me and I will write them the best way I can…. So damn Russell, damn Yeats,... damn editors, damn free-thinkers, damn vegetable verse and double damn vegetable philosophy!”

Bloom’s snide remarks in this passage are part of a larger pattern of rejection and criticism of the Irish Literary Revival and Æ in particular throughout Ulysses. Æ will even figure into Stephen’s debate over Shakespeare in the next episode of the novel, “Scylla and Charybdis.” There’s more to Bloom’s observations in this passage than some residual bile from Joyce’s youth, but it is definitely a contributing factor. In any case, Bloom is willing to entertain some mildly metaphysical ideas about food. He takes the adage “you are what you eat” quite literally:

“I wouldn’t be surprised if it was that kind of food you see produces the like waves of the brain the poetical. For example one of those policemen sweating Irish stew into their shirts you couldn’t squeeze a line of poetry out of him. Don’t know what poetry is even. Must be in a certain mood.”

A vegetarian diet that leads to a windy constitution of the body also leads to an “etherial” mind, coalescing into poetry. Bloom sharply contrasts Æ with the constables he saw on the other side of Trinity College earlier in the episode, waddling to and from the police station full of stew. Their meaty, sloppy feed turns their brains to meat rather than ether. Their inability to “squeeze a line of poetry out ” has a certain excretory implication as well. A sort of constipation of the spirit. Bloom immediately differentiates himself from the meathead constables by composing a quick couplet about the seagulls he met earlier:

“The dreamy cloudy gull

Waves o’er the waters dull.”

Curiously, the gulls are dreamy and cloudy, like the opal hushers, despite their all-fish diet.

Long before Æ, Leopold Bloom, or the gulls, diet was believed to affect the spirit. The ancient Greeks saw a strong connection between the food a nation ate and the character of that nation. Such a connection is evident in The Odyssey in the contrast between the Lotus Eaters and the Lestrygonians. Æ and his poets are more at the Lotus Eaters end of the spectrum rather than the Lestrygonian end, occupied instead by the men Bloom observes in the Burton restaurant in this episode. In less ancient Irish history, food also had transformative power to alter the spirit. Towards the end of “Lestrygonians,” Bloom thinks:

“They say they used to give pauper children soup to change to protestants in the time of the potato blight.”

The nourishment of a simple bowl of soup puts the eternal soul of these starving children in jeopardy, this logic concludes, resulting in a stigma against those who “took the soup” in the Famine years. I think it is unethical to begrudge a starving person a bowl of soup, but this persistent cultural belief illustrates the difference in material and spiritual nourishment by even a common food item. Rejection of protestant soup was a rejection of spiritual transformation. Likewise, Vegetarianism for theosophists in this era was a largely spiritual exercise, with less of a focus on animal welfare or environmental concern that accompanies modern vegetarianism. Bloom’s worldview is strongly materialist. Even when he tries to explain metempsychosis to Molly, he botches the explanation by explaining metamorphosis instead. Metempsychosis describes a spiritual transition, while metamorphosis is a physical transformation. Ironically, if Bloom were willing to talk to Æ rather than quip from afar, he could get the answers he seeks in relation to spiritual metempsychosis.

In a materialist worldview, eating meat leads to a physical transformation of animals into meat which, guided through the digestive system by peristalsis, transforms into shit and exits the body to enrich the soil, as shown in the functional duty of the rat in Glasnevin Cemetery back in “Hades.” By placing vegetarians like Æ in opposition to the material reality of the cycles of the natural world, Joyce demonstrates their avoidance of reality. Depicting even the dirty and ugly parts of life was central to Joyce’s artistic vision. He saw Revivalist writers like Æ as out of touch with the reality of most Irish people’s lives as they buried themselves in esoteric ideas and mythological imagery. In Joyce’s view, their insubstantial art is reflected by their diet. They would rather spiritually connect with the false mimicry of nutsteak than the Truth of rumpsteak.

Bloom changes his tune a few pages later after he is confronted with the lestrygonian carnage of lunch at the Burton restaurant. Just before entering Davy Byrne’s moral pub, he thinks:

“After all there’s a lot in that vegetarian fine flavour of things from the earth garlic of course it stinks after Italian organgrinders crisp of onions mushrooms truffles.”

Along with this newfound positivity, Bloom considers the ethics of eating meat:

“Pain to the animal too. Pluck and draw fowl. Wretched brutes there at the cattlemarket waiting for the poleaxe to split their skulls open. Moo. Poor trembling calves. Meh. Staggering bob. Bubble and squeak. Butchers’ buckets wobbly lights. Give us that brisket off the hook. Plup. Rawhead and bloody bones. Flayed glasseyed sheep hung from their haunches, sheepsnouts bloodypapered snivelling nosejam on sawdust. Top and lashers going out. Don’t maul them pieces, young one.

Hot fresh blood they prescribe for decline. Blood always needed. Insidious. Lick it up smokinghot, thick sugary. Famished ghosts.”

Scenes from Bloom’s former gig working for Joe Cuffe in the Dublin cattle market twist in his mind. He was a bit flippant earlier about theosophists fearing the haunting eyes of a cow, but Bloom is now unable to escape the guilt sending these gentle animals to meet a grisly death. One of Bloom’s defining traits is his abundant empathy, in particular his empathy toward animals. His heart goes out to his hungry cat, the overworked horses in the street and even a little stray dog that he brought home once, much to Molly’s dismay. Bloom is indeed followed through all eternity by the eyes of these cows.

It’s no surprise that Bloom worked in the cattle industry, however temporarily. According to scholar Peter Adkins, at the turn of the twentieth century, around two thirds of Irish wealth came from cattle, with more than 50% of Ireland’s land surface given over to cattle farming. This explains the depth of Mr. Deasy’s concern over foot and mouth disease back in “Nestor”; a devastating epidemic among cattle could seriously destabilize the economy of the United Kingdom. Bloom recalls back in “Hades”, however, that Ireland did not profit nearly as much as Britain off the cattle trade. The herds brought to the Dublin cattle market were transported alive across the sea to Britain, where they were butchered and sold. From “Hades”:

“For Liverpool probably. Roastbeef for old England. They buy up all the juicy ones. And then the fifth quarter lost: all that raw stuff, hide, hair, horns. Comes to a big thing in a year. Dead meat trade. Byproducts of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine. Wonder if that dodge works now getting dicky meat off the train at Clonsilla.”

“Dicky meat” refers to the black market meat trade in Ireland. Britain fed itself on the labor of Ireland, leaving the Irish themselves nothing but “dicky meat.” In the economic context of the British Empire, Ireland was considered one big pasture and cattle more valuable than Irish laborers. Throughout the 19th century, Irish tenant farmers were evicted from their land by landowners who thought converting the land to grazing was more profitable. James Joyce described some of the political unrest that followed such dehumanizing cruelty on the part of the ruling class in a 1907 essay entitled “Ireland at the Bar.” From 1905 onward, rural Irish people began illegally moving cattle and other livestock from land that could have been used to grow food crops. Joyce wrote that these “cattle drivers” were mounting a protest against landowners after “seeing the pastures full of well-fed cattle while an eighth of the population is registered as being without sustenance.”

The cattle trade resulted in violence against animals, both human and non-human. Eating meat, being the person who benefited from the violence, meant you were at the top of the societal food chain. It meant you could afford to eat meat, first of all. Eating meat was also associated with masculine virility, dominance over the natural world, and over cultures perceived as less-civilized or less advanced. Additionally, in a Christian worldview, only humans have souls, so there is less moral quandary over destroying animals. Eating meat, then, was a way to differentiate the men of the British Empire from the heathens they subjugated. This same worldview is played out even today via online fads like Jordan Peterson’s carnivore diet and “fitness” influencers like the now dethroned Liver King. (Side note: an all meat diet is just as unhealthy as fruitarianism. I am not endorsing the carnivore diet).

In this climate, to eschew meat is to eschew masculinity itself. Bloom is feeling particularly insecure in his masculinity on Bloomsday due to Molly’s impending “music lesson” with Blazes Boylan. His insecurity is thrown into high relief by seeing Æ who is comfortable not only openly behaving in ways that are not traditionally masculine, but also whose physical appearance loudly proclaims his bohemian status. Bloom feels like an outsider as a Jewish man and as someone perceived as weak or effeminate by his peers. While Æ is able to choose his outsider status, Bloom’s is foisted on him by a bigoted society. Bloom tries his best to assimilate, but can never convincingly be “just one of the guys.” For these reasons, the sight of Æ triggers this pain and insecurity in Bloom (and I suspect by extension, in James Joyce), though he doesn’t realize it consciously. Bloom lashes out at Æ to distance himself from this bohemian weirdo, hoping to edge himself just a little higher in the societal pecking order. Of course, no one but Bloom (and us) can hear his thoughts, but he carries out this ritual of performative masculinity nonetheless. Even as he concedes that vegetarians actually make some good points, he never thinks that he was wrong to poke fun at Æ and Lizzie.

At long last, Bloom settles into a vegetarian lunch in Davy Byrne’s moral pub. Prior to entry he even shrugs, “Never know whose thoughts you’re chewing.” We might want to consider Bloom’s burgundy and gorgonzola a W for team vegetarian, but Bloom still tucks into a plate of liver and mashed potatoes at the Ormond Hotel at dinner time, which he thinks of as “meat fit for princes.” Or maybe a Liver King? Either way, Bloom doesn’t consider his gorgonzola sandwich vegetarian at all. Circumspect as ever, he acknowledges. “Cheese digests itself.” He’s referring to rennet, a substance used to separate curds and whey in cheese production. It is made from the stomachs of calves, thus it could theoretically digest the cheese it’s used to make. Bloom is aware of the barbarity of the system he lives in, but he is not willing to live radically outside it. In the end, he pushes his empathy aside in favor of the foods he loves. Afterall, if he really wanted a truly vegetarian lunch, he could have just gone to the vegetarian restaurant.

Further Reading:

Adkins, P. (2017). The Eyes of That Cow: Eating Animals and Theorizing Vegetarianism in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Humanities, 6 (46). Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/6/3/46

Annino, E. Joyce Restyles The Times. James Joyce Digital Interpretations. Retrieved from https://jamesjoyce.omeka.net/exhibits/show/vegetarianism-in--lestrygonian/vegetarianism-in--lestrygonian

Carlson, L. (2018, Jan 12). A Case for Kale: Vegetarianism in Victorian England. The Feast podcast. Retrieved from http://www.thefeastpodcast.org/2018/1/11/e0d34emxze70bjr6hrbleztkq2u1k2

Dwyer, F. (2022, Mar 17). Could you survive on a pre-Famine Irish diet? I tried.... The Irish History Podcast. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/v9BLZaXGSfw

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Freedman, A. (2009). Don’t eat a beef steak": Joyce and the Pythagoreans. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 51(4), 447–462. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40755555

McGrath, S. (2013, May 21). Some notes on the history of Vegetarianism in Dublin Pt. I (1866 – 1922). Come Here to Me. Retrieved from https://comeheretome.com/2013/05/21/some-notes-on-history-of-vegetarianism-in-dublin-pt-i-1866-1922/

Rosenquist, R. Bloom’s digestion of the economic and political situation. Flashpoint Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.flashpointmag.com/lestrgon.htm

Tucker, L. (1984) Stephen and Bloom at Life’s Feast. Ohio State University Press.

Yared, A. (2009). Eating and Digesting “Lestrygonians”: A Physiological Model of Reading. James Joyce Quarterly, 46(3/4), 469–479. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20789623