Up the Boers!

As Leopold Bloom passes beneath Tommy Moore’s roguish finger on his long walk to lunch in “Lestrygonians”, Ulysses’ eighth episode, a flock of cops catches his attention:

Tommy Moore, January 2023

“A squad of constables debouched from College street, marching in Indian file. Goosestep. Foodheated faces, sweating helmets, patting their truncheons. After their feed with a good load of fat soup under their belts. Policeman’s lot is oft a happy one. They split up in groups and scattered, saluting, towards their beats. Let out to graze. Best moment to attack one in pudding time. A punch in his dinner. A squad of others, marching irregularly, rounded Trinity railings making for the station. Bound for their troughs. Prepare to receive cavalry. Prepare to receive soup.”

Bloom casts a snarky eye on these overfed, spoiled house cats biding their time between meals. Bloom remarks that they are “bound for their troughs,” invoking the porcine imagery often used to denigrate police. He also twice imagines them slurping soup, implying they “took the soup.” This expression goes back to the time of the Famine in the 1840’s, when Protestants would offer starving Catholics soup or other food in exchange for conversion. While I personally think it’s ethically dubious to begrudge a starving person a bowl of soup, the term “souper” came to mean a traitor - someone willing to sell their soul to the colonial enemy.

Bloom’s not ready to declare “all constables are bastards,” but his sarcasm implies that these men are creatures of the Crown. His ambivalence to the constables is a product of his class. The working class and the impoverished were more likely to feel the business end of a police truncheon than a respectable middle class citizen like Bloom. He is able to see some of their more brutal actions as just doing their job. After all, Bloom has friends who work in and around Dublin Castle. A good example of this is how he uses his acquaintanceship with Corny Kelleher and Simon Dedalus to keep Stephen out of police trouble in “Circe”. These constables are ordinary Irish men, just like Bloom and his friends, but the Royal Irish Constabulary was also an arm of the colonial government charged with enforcing the laws of the Empire in Ireland. As the constables recede from view, Bloom’s memory flashes to a time when he ran afoul Johnny Law:

“He gazed after the last broad tunic. Nasty customers to tackle. Jack Power could a tale unfold: father a G man. If a fellow gave them trouble being lagged they let him have it hot and heavy in the bridewell. Can’t blame them after all with the job they have especially the young hornies. That horsepoliceman the day Joe Chamberlain was given his degree in Trinity he got a run for his money. My word he did! His horse’s hoofs clattering after us down Abbey street. Lucky I had the presence of mind to dive into Manning’s or I was souped. He did come a wallop, by George. Must have cracked his skull on the cobblestones. I oughtn’t to have got myself swept along with those medicals. And the Trinity jibs in their mortarboards. Looking for trouble…. Police whistle in my ears still. All skedaddled. Why he fixed on me. Give me in charge. Right here it began.”

Bloom recalls a real event from Dublin’s turbulent history - a massive protest movement sparked by the Boer War, a largely forgotten, “absentminded” conflict that roused the passions of Irish nationalists and steered the course of early 20th century Irish politics. The Boer War was a fading but recent memory by 1904; Bloom’s ears are still ringing with the shrill shrieks of phantom police whistles. He thinks, “I oughtn’t to have got myself swept along with those medicals.” Was our pragmatic, gentle Bloom a bit more radical in his slightly younger days? Or was he merely overwhelmed by the sudden onset of a riot while passing innocuously through Dublin’s city centre? There’s just enough ambiguity in Bloom’s statement, paired with his own conflicting statements about the Boer War throughout Ulysses, to give us pause. If we look into the historical context, perhaps we can find some answers.

The Second Boer War, beginning in October 1899 and lasting until 1902, was a territorial struggle between two colonial powers in modern South Africa. Both British settlers and Dutch settlers, known as Boers, claimed territories on the south tip of the African continent. When gold was discovered in Boer territory, predictable tensions rose between the two colonizers, and the British invaded Boer territory. The war was incredibly gruesome, and among other atrocities, introduced the first concentration camps. Public response in Britain and Ireland polarized along political lines. Loyalists to the imperial government saw supporting the war effort as a patriotic duty, while critics of the government, such as Irish Nationalists, rallied behind the Boers, with whom they felt a political kinship in the struggle against the British Empire.

Christiaan De Wet

There’s an unavoidable cognitive dissonance to supporting the Boers against the British for an Irish anti-colonialist. The Boers were also colonizers who stole land and resources from the indigenous people of southern Africa; their descendants would one day commit the injustices of apartheid alongside their Anglo countrymen. Additionally, the Boer leader Christiaan De Wet, who figures in Bloom’s recollection (“Three cheers for De Wet!”), held the title of State President of the Orange Free State. The “Orange” part of the title is a reference to the same William of Orange lionized by the Orange Order and other Unionist, anti-Catholic groups in Ireland, the historic enemies of Irish nationalists. It’s a case of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” The Irish independence movement in the late 1890’s was beginning to build steam, and the Boer War was a cause they could throw their momentum behind as a proxy for Irish independence.

In September 1899, the Transvaal Committee met for the first time in the rooms of the Celtic Literary Society in Dublin to mount a resistance to the impending war. The prime movers included Maud Gonne and John O’Leary, and attendees included Sinn Fein founder Arthur Griffith and Easter Rising leader James Connolly. Scholar P.J. Mathews described the Transvaal Committee as a precursor to Sinn Fein itself as this cause united various nationalist factions that otherwise would have been at political odds. Other members of the committee, such as John MacBride, traveled to South Africa to support the Boers in battle. Boer War battles were often fought with Irish soldiers on both sides, some supporting the Empire, some supporting the Boers.

Joe Chamberlain

For those who remained home in Dublin, opposition to the Boer War manifested as massive demonstrations against the war, the size and violence of which would remain unparalleled until the Dublin Lockout in 1913. Gonne and O’Leary’s rallies in Dublin’s city centre drew tens of thousands protesters into the streets. Civil unrest came to a head in December 1899 when Trinity College conferred an honorary degree on Joseph “Joe” Chamberlain, noted monocle enthusiast and father of Neville. Chamberlain had been an especially enthusiastic saber-rattler in the run up to the Boer War and a strenuous opponent to Irish Home Rule.

This is the protest that Bloom got swept up in. Protesters thronged around the gates of Trinity College. The police forced them down Dame St., away from the college. Police on foot charged the crowd with batons drawn, while mounted police armed with sabers eventually broke up the crowd. An image run in the French Le Petit Journal depicts the struggle raging on the steps of Trinity College, police and protesters locked in combat beneath the flag of Transvaal. Mathews wrote that a young “Sean O’Casey recount[ed] how he made use of a flagpole to unseat a policeman before retreating to a nearby pub.” I don’t think James Joyce claimed to attend the event or knew of O’Casey’s jousting act, but Bloom’s anecdote bears some curious similarities:

Image of the protest from Le Petit Journal

“That horsepoliceman the day Joe Chamberlain was given his degree in Trinity he got a run for his money. My word he did! His horse’s hoofs clattering after us down Abbey street. Lucky I had the presence of mind to dive into Manning’s or I was souped. He did come a wallop, by George. Must have cracked his skull on the cobblestones.”

Bloom’s dramatic memory isn’t the only time the Boer War or South African affairs more broadly appear in Ulysses. In the first episode, “Telemachus”, Buck Mulligan quips to Stephen Dedalus about their irritating English houseguest Haines’ father:

“His old fellow made his tin by selling jalap to Zulus or some bloody swindle or other.”

It’s clear from the earliest pages of Ulysses that business in South Africa is a chance for white settlers to make a mint exploiting the indigenous residents, including Haines’ father scamming the colonized people in southern Africa for profit. European colonialism was often framed as a “civilizing” endeavor; Europeans were somehow helping their colonized subjects by teaching them European values, economics and, of course, Christianity. It’s clear from the way characters in Ulysses talk about British incursion into South Africa that average Dubliners did not see it this way. They knew that colonization in Africa was a purely economic project. The Boer War only served to underscore this fact, as it was a war in which white Christian Europeans fought other white Christian Europeans over land in Africa, purely for economic greed and resource extraction.

Of course, those loyal to the Crown had different ideas. A propaganda campaign was mounted in the United Kingdom to drum up support for the war. Rudyard Kipling wrote the poem “The Absentedminded Beggar” as what he called a “catchpenny verse”, meaning it should catch as many pennies as possible for the war effort. Kipling gave the poem to Alfred Harmsworth (“Harmsworth of the farthing press” as he’s called in “Aeolus”), who printed it in his newspaper, The Daily Mail. Though “The Absentminded Beggar” was a smash hit, even set to music by Arthur Sullivan, it wasn’t enough to polish the image a bloody, scorched earth campaign and the use of concentration camps by the British. Stephen quips to John Eglinton in “Scylla and Charybdis” that Hamlet could be renamed “The Absentminded Beggar”, his own snarky reminder that they are praising an Englishman despite the Irish nationalism of the Dublin literary set. Stephen moves on to English poet Algernon Swinburne:

“Khaki Hamlets don’t hesitate to shoot. The bloodboltered shambles in act five is a forecast of the concentration camp sung by Mr Swinburne.”

Stephen partially quotes a line from Algy’s poem “On the Death of Colonel Benson”:

“Toward whelps and dams of murderous foes, whom none

Save we had spared or feared to starve and slay.”

Swinburne commemorates and celebrates the merciless slaughter of Boer civilians by the British army in this poem. The brutality of the war is not concealed in the jingoistic poetry of the era, but rather celebrated in a show of patriotic fervor, which Stephen openly criticizes to his cohorts in the Library. In real life, James’ father John Joyce had a habit of picking fights with “stolid Englishmen” about the Boer War, possibly a habit that Stephen is reflecting here.

Much later, as Bloom tries to sober up Stephen in the cabmen’s shelter in “Eumaeus”, the once-invincible Skin-the-Goat elucidates a Boer War conspiracy theory:

“One morning you would open the paper, the cabman affirmed, and read: Return of Parnell. He bet them what they liked. A Dublin fusilier was in that shelter one night and said he saw him in South Africa…. Dead he wasn’t. Simply absconded somewhere. The coffin they brought over was full of stones. He changed his name to De Wet, the Boer general. He made a mistake to fight the priests. And so forth and so on.”

De Wet, who the protesters cheered for in 1899, was the secret identity of the fallen Irish savior, Charles Stewart Parnell. Embers of nationalist outrage sparked by the Boer War opposition movement still glow in 1904. The flimsy hope that Parnell somehow faked his death and would once more deliver the Irish from imperialist evil is dressed up in the story of De Wet, another leader to whom hopes of a British defeat were once attached.

Mulligan, Dedalus and even Skin the Goat’s worldview come into focus in these passages, but what do we know about Bloom’s views of the war? What comes across in his memory of the December 1899 protest first and foremost is regret: “I oughtn’t to have got myself swept along with those medicals.” Does this mean that Bloom was an apolitical bystander bumbling through town and was suddenly surrounded by a crowd of angry students? Stuart Gilbert gave Bloom some agency, stating “he got involved in a crowd of young medicals demonstrating against the Boer War.” Frank Budgen, on the other hand, described Bloom as “an innocent passer-by on that occasion,” going on further to say Bloom “had no patience with the rebel politics of youth.” Sure enough, Bloom scoffs at the young protesters:

“Silly billies: mob of young cubs yelling their guts out…. Few years’ time half of them magistrates and civil servants. War comes on: into the army helterskelter: same fellows used to. Whether on the scaffold high.”

Bloom astutely notes that some youthful political radicals become more conservative as they age and take respectable jobs. It’s easy to see a parallel in young people who were free-wheeling hippies in the 1960’s but voted for Reagan in the ‘80’s. It’s also easy to see how Bloom’s sympathies might dry up if he had turned up at the protest volitionally, but then got in over his head when the police turned on the crowd. I don’t agree with commentators who say that it would be totally out of character for Bloom to attend a political protest. He has a streak of stubborn righteousness in him and is willing to defend an underdog, even when it’s more prudent to remain silent. We see this most clearly when he goes toe to toe with the Citizen in “Cyclops,” at the risk of his own safety. In another passage in “Cyclops,” we also learn about a rumor from John Wyse that “...it was Bloom gave the ideas for Sinn Fein to Griffith….” It’s fun to speculate that Bloom might have given Arthur Griffith this idea during a brief stint in the pro-Boer protest movement, though there’s no reason to think this is what Joyce actually meant.

On the other hand, Bloom openly professes support for the British side throughout Ulysses. When the crowd turns on Bloom in “Circe,” he is accused of booing Joe Chamberlain. Bloom defends himself by emphasizing his loyalist cred:

“BLOOM: (His hand on the shoulder of the first watch.) My old dad too was a J. P. I’m as staunch a Britisher as you are, sir. I fought with the colours for king and country in the absentminded war under general Gough in the park and was disabled at Spion Kop and Bloemfontein, was mentioned in dispatches. I did all a white man could.”

Bloom’s got the wrong Gough.

Bloom’s attempt at self-preservation is fairly transparent, though. He refers to the Boer War as “the absentminded war,” clearly a reference to Kipling’s poem. The term “absentminded war” implies a senselessness to the war, though, which undercuts his pro-British message. In classic Bloom fashion, he botches another detail - “general Gough in the park”. There was indeed a General Gough who fought in the Boer War, but he is not the General Gough whose statue stands in Phoenix Park. Phoenix Park Gough fought in the Napoleonic War and certainly one of Boer War Gough’s soldiers would recognize the difference.

The best case to be made for Bloom supporting the British side in the Boer War is that he has an investment in government stock, described in “Ithaca” as “certificate of possession of £900, Canadian 4% (inscribed) government stock (free of stamp duty)”. A Boer victory over the British would therefore hurt Bloom financially, and would give him reason to hope for their victory. From “Oxen of the Sun”:

“During the recent war whenever the enemy had a temporary advantage with his granados did this traitor to his kind not seize that moment to discharge his piece against the empire of which he is a tenant at will while he trembled for the security of his four per cents?”

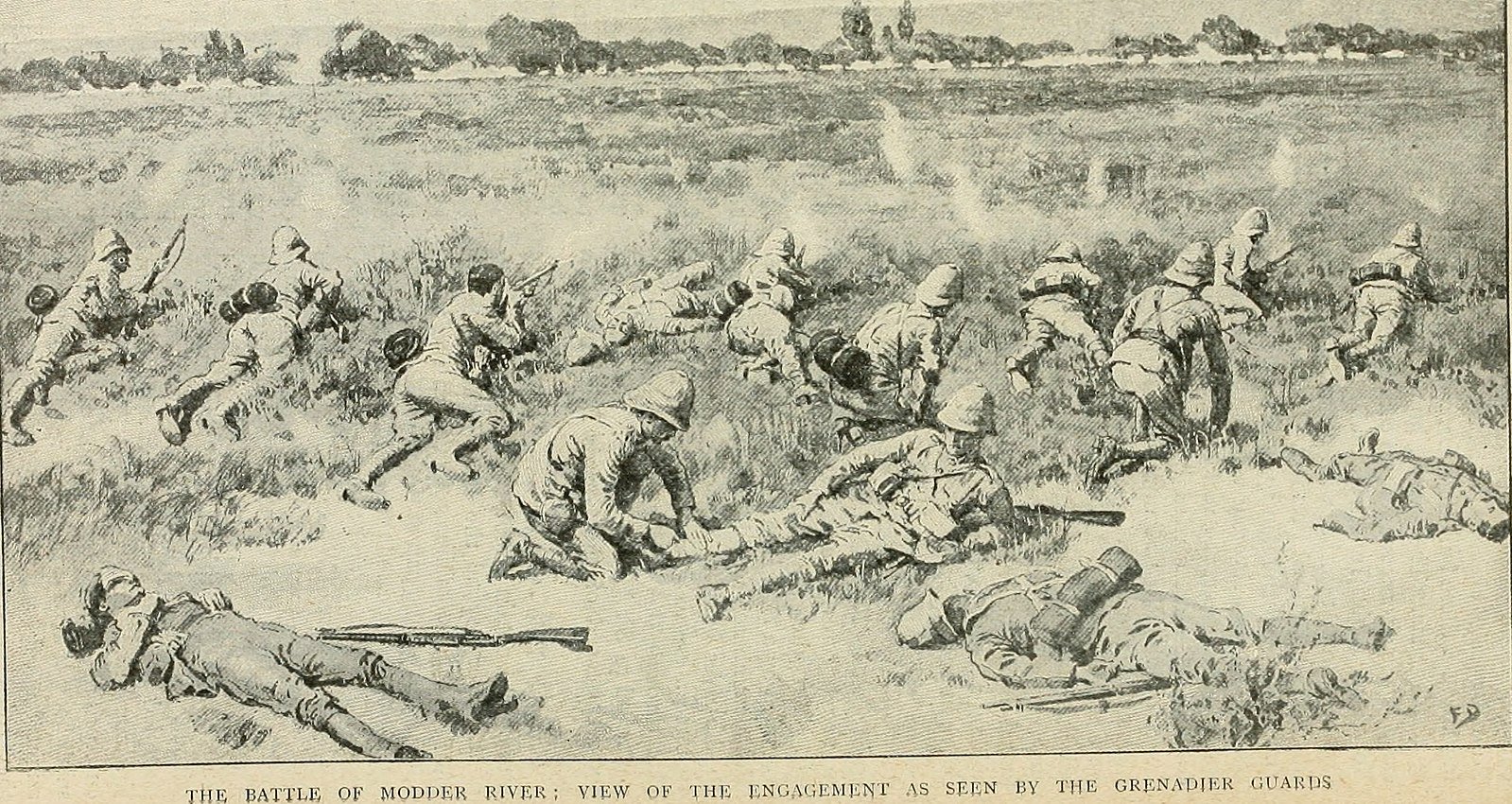

There’s one final biographical detail that I think might have pushed Bloom volitionally into the streets in December 1899. Bloom reminiscences from time to time on Bloomsday about his childhood friend Percy Apjohn. We learn in “Ithaca” that Percy was killed in action at the Modder River, the site of a Boer War battle that took place just a month before in November 1899. While there is plenty of reason to think of Bloom as ambivalent about the politics of the Boer War in 1904, we know that he can be deeply undone by the loss of someone close to him. We know he lost his job at Wisdom Hely’s in the wake of Rudy’s death. Perhaps it was the senseless squandering of his dear old friend’s life in some absentminded war that moved Bloom to a rare radicalism, however temporary. With this in mind, Bloom’s political rage was perhaps the rage of grief at the injustice of the loss of Percy and all the young men like him in both armies.

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, R. (1999). The Absent-Minded War: The Boer War in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Kunapipi, 21 (3), 81-89. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232895035.pdf

Booker, K. (2000). Ulysses, capitalism, and colonialism - Reading Joyce after the Cold War. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/2n883959

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Fallon, D. (2015, Dec 26). A riot on College Green, 1899. Come Here To Me! Retrieved from https://comeheretome.com/2015/12/26/a-riot-on-college-green-1899/

Fordham, F. (2016). James Joyce and Rudyard Kipling: Genesis and Memory, Versions and Inversions. European Joyce Studies, 25, 181–200. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871411

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Mathews, P. J. (2003). Stirring up Disloyalty: The Boer War, the Irish Literary Theatre and the Emergence of a New Separatism. Irish University Review, 33(1), 99–116. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25517216

Raleigh, J.H. (1977). The Chronicle of Leopold and Molly Bloom. Retrieved from

https://archive.org/details/chronicleofleopo00john/page/173/mode/2up

Rosenquist, R. Bloom’s digestion of the economic and political situation. Flashpoint Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.flashpointmag.com/lestrgon.htm

Temple-Thurston, B. (1990). The Reader as Absentminded Beggar: Recovering South Africa in “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 28(1), 247–256. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25485129